Protestant American and a Myth of National Identity

American interest in Israel/Palestine or the “Holy Land” may seem like a 20th and 21st century phenomenon, but in fact, America experienced a “Holy Land” mania in the 19th century. What was the root of American interest in Palestine, or the “Holy Land”? How could there be so much interest in a place that so few had traveled to? While there are several interconnected reasons yet different reasons, they were all reflections of America’s core identity in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Many of America’s original settlers in the 17th and 18th centuries were Protestants seeking religious refuge, and by the early 19th century, the population of the United States was both religiously and culturally undergirded by a zealous Protestantism. North America provided an opportunity for a fresh beginning, a clean slate unencumbered by the limitations of the Old World. This political and social reality would be re-internalized through the appropriation of Palestine in the American imagination to create a myth of identity and history. This appropriation and identification with the physical land of Palestine led to an intense interest in Palestine, what can be called a “Holy Land” mania. Literature – but also works of art and other cultural products – pertaining to Palestine and specifically traveling to Palestine became incredibly popular among the American public, mediating Americans’ understanding of Palestine.

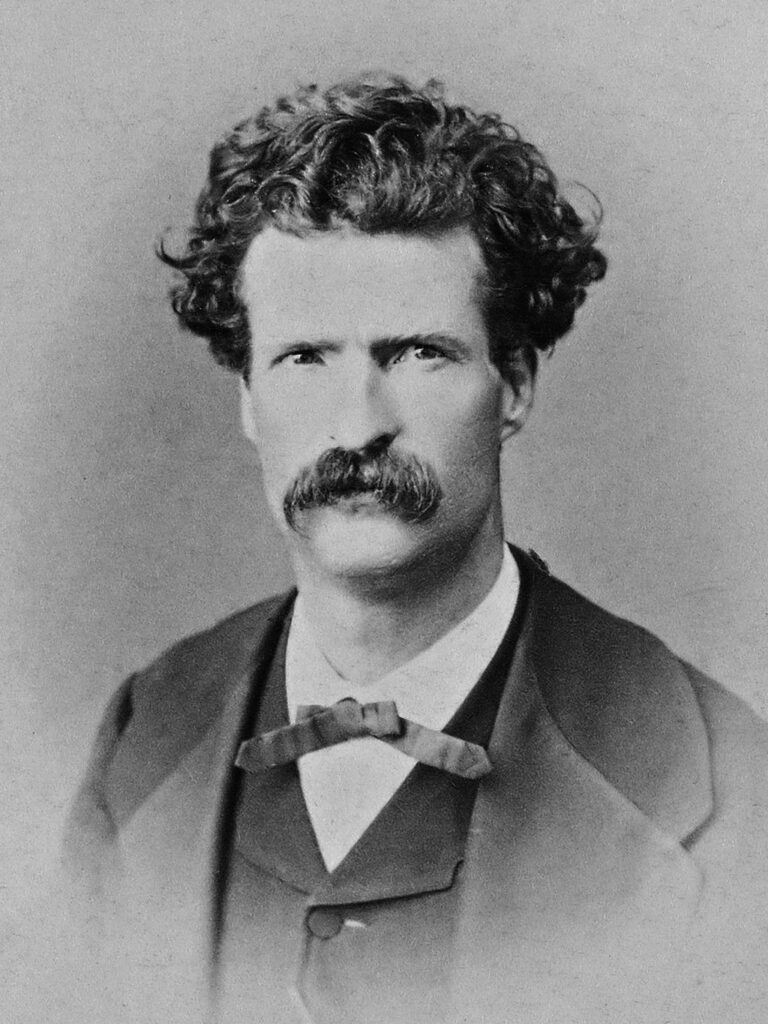

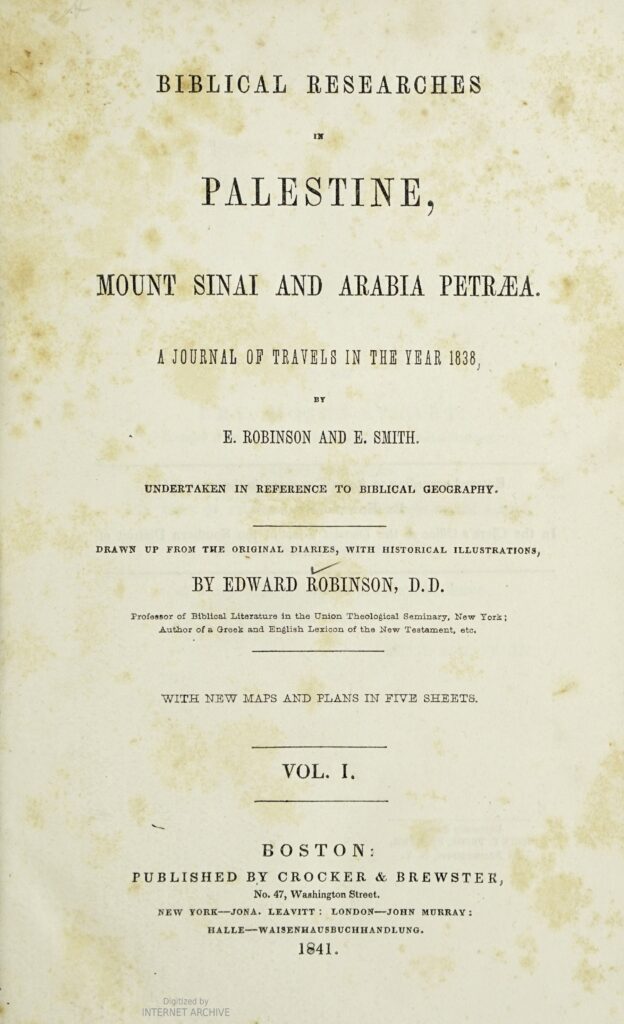

Three of arguably the most significant works of “Holy Land” literature in the 18th century all represent a different lens of the appropriation of Palestine in the American imagination. Edward Robinson, a theologian, published Biblical researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea in 1841 with assistance from missionary and Arabist Eli Smith; William McClure Thomson, a veteran missionary, published The Land and the Book: or Biblical Illustrations Drawn From the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery of the Holy Land in 1859; and Mark Twain – the journalist, satirist, and author — published The Innocents Abroad, or The New Pilgrim’s Progress in 1869.

The allure of Palestine for figures like Robinson, Thomson, Twain, and many other Americans, stemmed from a deeper, symbolic resonance and anxieties. Their journeys to Palestine were not primarily about understanding its people or its development; rather, they sought to validate and reinforce their own American identities rooted in settler colonialism, Protestantism, and the notion of American exceptionalism, all within a sacred geography. This sacred geography could function almost as a blank canvas, with greater resonance, for theologians, missionaries, and well-endowed travelers. This underscores how the imaginary, embodied by the romanticized idea of the Holy Land — which was often quickly disappointed — served as a conduit for projecting American ideals and aspirations onto a distant, mythologized landscape.

When Alexis de Tocqueville traveled to America in the 1830s, he observed that in no other nation does Christianity wield a stronger sway over the hearts of its people than in America. Americans were exceptionally well-versed in the Bible; many saw North America as a New Jerusalem. They saw their own journey and settler colonial Westward expansion paralleled in the Israelites’ story in the Old Testament. And like the covenant the Israelites had with God, many Americans couched their Westward Expansion in covenantal language. American travelers in Palestine saw Arabs as Native Americans.

The “Holy Land” was a geographical myth in the same sense that the Western frontier was a geographical myth and a geography of ritual. Palestine was a place of religious ritual, and the Western Frontier was a place of civil ritual where the idealized American man was formed. Both the North American continent and Palestine were sacred geographies that would serve as ritualized locations, settings for divine scenarios.

For the vast majority of Americans Palestine was an imagined locale, mediated through textual encounters that themselves distorted by their authors Biblically grounded identities.

Edward Robinson – Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea

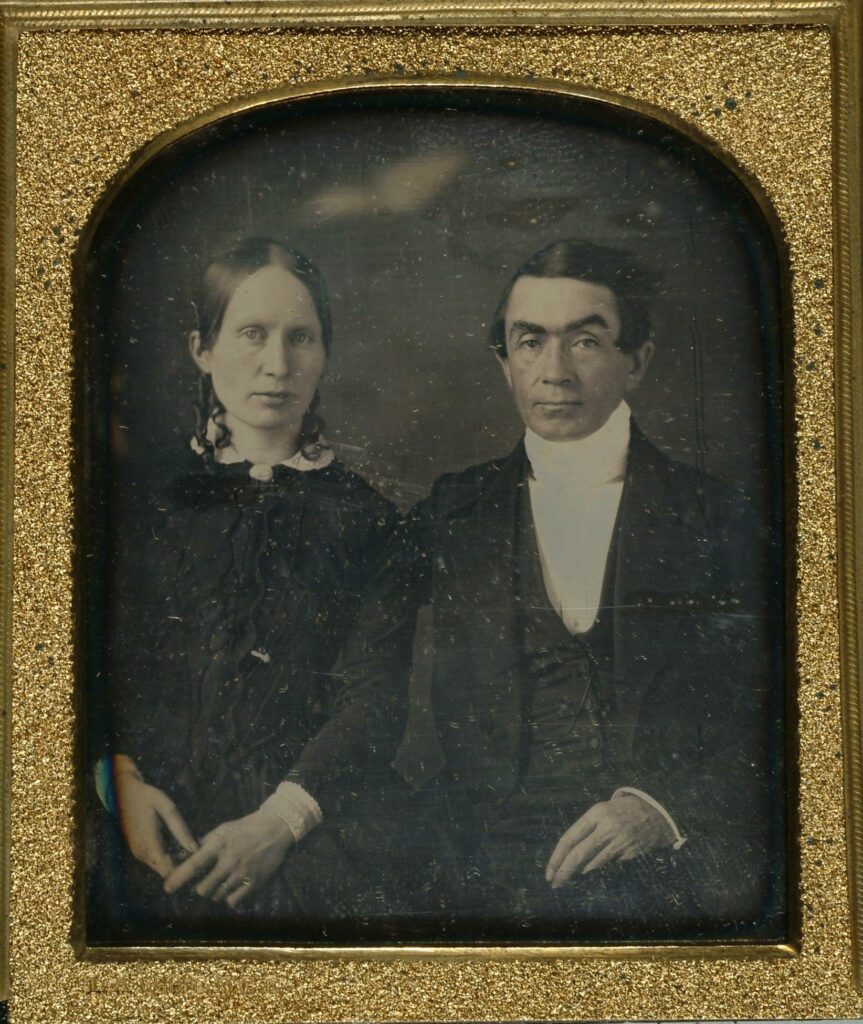

Somewhat erroneously called the “father of biblical archeology,” Edward Robinson was born in Connecticut in 1794 and studied at the Andover Theological Seminary, subsequently becoming an instructor there. Later, he left Andover and became a professor of Biblical literature at Princeton Theological Seminary. Robinson was arguably the first person in the modern period with comprehensive training in Biblical Studies to travel to Palestine with the geography of the Holy Land as his primary aim.

Eli Smith, a previous student of Robinson’s, headed the mission and Beirut and had considerable knowledge of Arabic and Arab culture. Smith served as Robinson’s guide throughout Palestine, and without him, Robinson’s 1837 journey would likely not have resulted in such a thorough and significant work. Nevertheless, Robinson had a rudimentary knowledge of Arabic.

Robinson, on a geographical mission, and Smith, on a religious one, still wrote in Biblical Researches in support of political control of Palestine. Not only that, but foreshadowing contemporary imperial rhetoric pertaining to the Middle East, Robinson claimed that the “Palestinians themselves desired Western control.” Indeed, the inhabitants everywhere appeared, for the most part, to desire that the Franks should send a force among them. They were formerly tired of the Turks; they were now still more heartily tired of the Egyptians; and were ready to welcome any Frank nation which should come, not to subdue, (for that would not be necessary,) but to take possession of the land.”

Robinson desired to see the land afresh. He was open in his contempt for the mythologized Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic sights and churches. A Presbyterian, he believed that non-Protestant denominations cultivated idolatry and superstition. Therefore Robinson’s mission, while undertaken in a systematic and meticulous way, was primarily a polemical one: to disprove the sacred nature of Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholics in the service of showing that Catholics and Eastern Orthodox taught false information.

However, while many American Protestants championed themselves as critical and rational thinkers, they rejected applying critical reasoning or the scientific method to the Bible itself. This points to another trend in American Protestantism: literalism. Literalism only increased the importance of the physical land of Palestine and turned it into an almost hermeneutical geography. This idea would be foundational to Thomson’s The Land and The Book.

Robinson’s project was in response to Protestant anxieties. Both in the United States and abroad. The sacred geography of Palestine and its place within the American imagination needed to be captured from Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox heretics. Additionally America was gaining more and more Catholic immigrants by the day and their religious inclinations needed to be refuted. Furthermore, Robinson and Smith utilized their knowledge of Arabic to identify previously unidentified biblical sights, harnessing their knowledge of the Orient to redefine and conquer it in the Biblical imagination.

William McClure Thomson – The Land and the Book: or Biblical Illustrations Drawn From the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery of the Holy Land

“The Land and the Book – with reverence be it said – constitute the ENTIRE and ALL-PERFECT TEXT, and should be studied together.” Thomson’s statement in the introduction of the book clearly lays out his thesis: The physical land of Palestine is necessary to properly understand the Old and New Testaments.

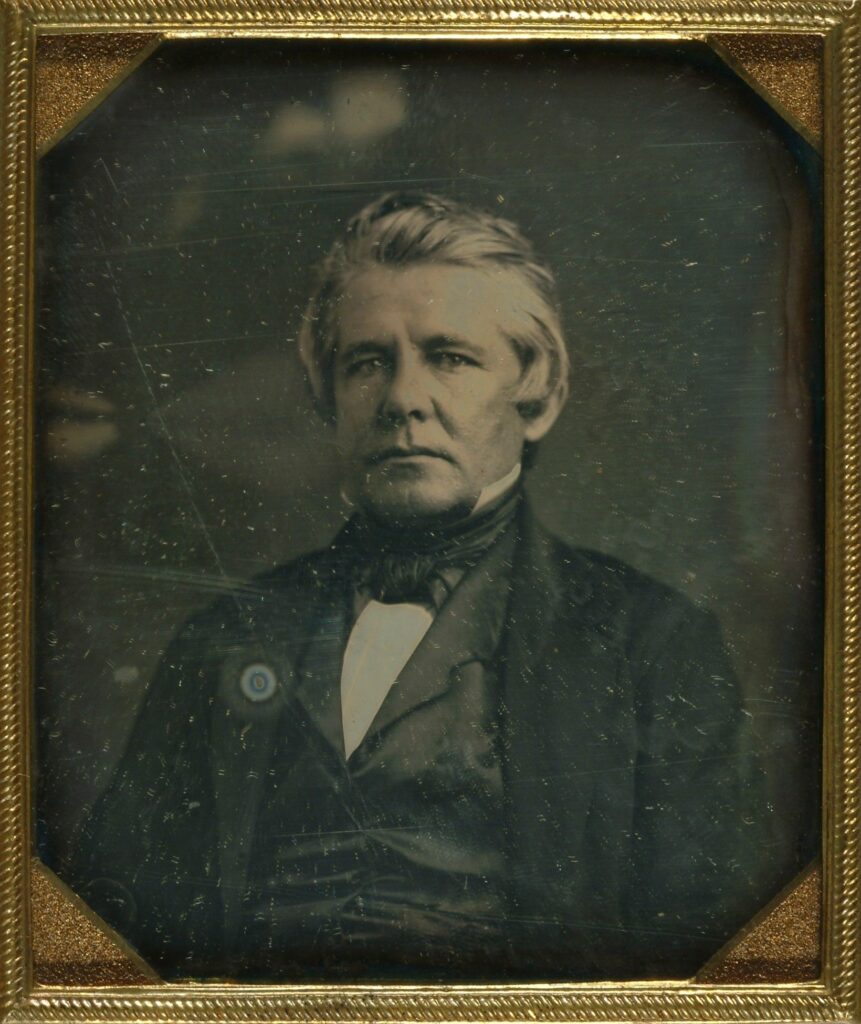

Thomson was born in Ohio in 1806 and attended Miami University and then Princeton Theological Seminary. When the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) decided to restart their missionary activities in the Levant, Thomson was one of the members of the group that arrived in Beirut in 1833. His mission was based in Beirut, but he had several opportunities to travel throughout Palestine before The Land and the Book was published in 1859. Thomson left Beirut, and the Levant, for good in 1876 and died in America in 1894.

Thomson wanted to “illustrate the word of God.” Palestine’s present situation and condition would illuminate the stories of biblical times; this was not restricted to history, geography, or other physical characteristics of the land but also the “manners and customs” of Palestinians. The dress, action, physical appearance, and overall presentation of Palestine’s inhabitants could be extrapolated to the characters in the bible. Thomson places a significant emphasis on historical continuity, an idea broadly held among American travelers, that the people of Palestine were nearly unchanged from their Biblical days. Thomson and his compatriots viewed the Holy Lands’ inhabitants through a romantic primitivism. They were inferior to Americans and often mere objects of fascination.

The book’s structure resembles a journey through Palestine, with Thomson’s alter ego acting as a knowledgeable guide and his naive companion asking questions that help guide the texts. When his naive companion points out with disdain the unusual and unfamiliar actions of the Palestinians, rather than simply confirming his stance like many other Holy Land travelers would, Thomson’s alter ego claims that these actions are nearly identical to those that would been done by Old Testament figures. Drawing parallels with Old Testament traditions, not New Testament ones, grants these religious rituals a degree of respect and comprehension yet concurrently consigns them securely to history. By association, the people themselves are almost also consigned to history. Protestant America is the new, enlightened community, a new Canaan.

It is also important to note as an aside that while Thomson’s book and this exhibit are not primarily about missionary activities, the Protestant missionary movement in the Middle East, from both North America and Great Britain, was a failure. Very few, if any, Muslims were interested in conversion – partially because they could be executed for such an action – and the missionaries themselves mostly stayed away from efforts to convert Muslims both because they were mostly unsuccessful and because, depending on the current authority in Palestine, it was a strictly prohibited activity. Another attractive target for Protestants, and especially evangelical missionaries, was the Jewish population in Palestine. It was a commonly held belief that the restoration of the Jews to Palestine and their conversion was necessary for the coming millennium. However, the Jewish community within Palestine in the 19th century – prior to the start of the first Aliyah in 1881 – probably numbered under 10,000 people or around 5% of the population. It was also an insular and deeply religious community that, for the most part, had no patience for the missionaries’ advances.

Consequently, the missionary movement’s primary targets were Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christians in Palestine. Thomson makes clear, akin to Robinson, that it was Protestantism versus the rest. Islam, Judaism, Roman Catholicism, and Eastern Orthodox Christianity were all illegitimate and deficient religions. They were Old World religions, and their followers were in desperate need of redemption.

Nevertheless, Eastern Orthodox Christians and Roman Catholics had a much richer history of engagement with Palestine. If Thomson wrote that “Palestine is one vast tablet whereupon God’s messages to men have been drawn, and graven deep in living characters by the Great Publisher of glad tidings, to be seen and read of all to the end of time,” then so far that “tablet” had been primarily seen and misread by false followers of Christ. Thomson and his fellow ABCFM missionaries saw themselves in Jesus’s own story: they were spreading the true word of God among an ignorant and resistant population.

Perhaps the most important theme of Thomson’s work is pilgrimage. In the 1830s and 1840s, American interest in the Middle East was rising, and that interest became easier to act upon. Thomson is creating a pilgrim’s manual so the increased number of American (and British) travelers can avoid the false sights of Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox admiration. Thomson’s literalism and comprehensive knowledge of the Old Testament (as well as the New) allow identifications of obscure persons and places. Both factors led Thomson away from population centers and towards the small villages and landscapes that he believed were the primary places of God’s encounters with humanity. Ideologically, it was also easier to highlight these areas than to appropriate the other Christian pilgrimage sites, like the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (which received intense disdain for Robinson, Thomson, and Twain).

Protestants believed they were entitled to their share of the Holy Land and by traveling through and documenting it, they were claiming possession. While this “possession” seems to be merely ideological, Thomson, Robinson, and many other Holy Land travelers were not shy in their sympathies for political change as well.

Mark Twain – The Innocents Abroad, or The New Pilgrim’s Progress

When Ulysses S. Grant made a world tour between 1877-1879, he brought with him to the Jerusalem three books: the Bible, the standard tour guide, and Mark Twain’s The Innocents Abroad. This would have been no surprise to any contemporary of Grant. The Innocents Abroad was wildly popular. It catapulted Mark Twain to fame, even outside of America, and was his best-selling work during his lifetime. While the depiction of his journey with his fellow travelers only make up a small portion of the book, Twain referred to Palestine as “the grand goal of the expedition.”

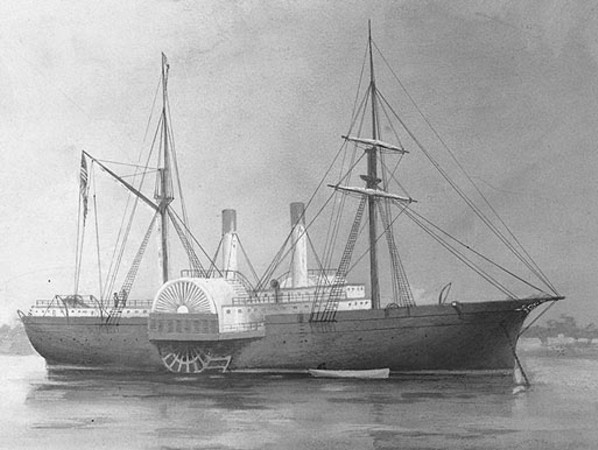

Twain, born and raised in Missouri in 1835, secured a spot on this Grand Tour through the backing of a Californian newspaper. They wanted him to document the first “large-scale tourist excursion cruise in American history.” Departing in 1867 aboard the Quaker City, a decommissioned Civil War Vessel, Twain, the humorous and often crass Southern turned Westerner, was the odd man out among wealthy and refined North-easterners. The Innocents Abroad is not only an important work for his treatment of Palestine and the way it relates to American identity, but also because it reflects broader currents in post-Civil War American life: a rising bourgeoisie capable of traveling and engaging with the wider world.

What makes Twain’s travelogue in Palestine stand out from other similar works is his irreverent and humorous take on his and his fellow passengers joruney. Mocking his fellow “pilgrims” reactions and the past Holy Land narratives that fueled them (referencing reactions copied from Robinson and Twain), Twain’s portrayal of Palestine could be even deemed irreligious. However, his narrative is still grounded in a Protestant American ethos. His knowledge of the Old and New Testament, and his respect for them, is displayed throughout his excursion as he makes continued long and detailed references to various Biblical stories in a serious and contemplative manor. His main issue throughout is the irrational, superstitious, and romanticized views of the Holy Land that had swept through his fellow travelers. He mocked the same Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox sites and shrines that Robinson and Thomson did. Twain also provides undue attention to the Jewish population reflecting a continued belief, or at least interest in the idea of Jewish restoration and conversion in the Holy Lands.

One of the most famous and oft-quoted portions of The Innocents Abroad is when Twain describes what he sees as Palestine’s desolation. Thomson, Robinson, and many other travelers to Palestine also referred to it in this way, referencing Deuteronomy, Chapter 29. The latter verses in this chapter say that the Land of Israel will fall into desolation because the Israelites, God’s chosen people, will break their covenant with God. At the same time, he was also mocking his predecessors in Palestine and his fellow travelers for their romanticized view of the land, dissociated from reality.

The character crafted by Mark Twain in The Innocents Abroad contributes to the emergence of a distinct literary persona: the American who frequently challenges established cultural norms and traditions, constantly seeking novelty and innovation while often causing disruption rather than embodying heroic traits. While this is still partially based on a Protestant insecurity shared by many of his more religious pre-Civil War compatriots, it is a more secular extension grounded in an Old World versus New World dynamic. Americans, their state, culture, and society are superior to Europe and the Orient; simply a feeling of American exceptionalism rooted in a Protestant Anglo-Saxon hubris.

Works Cited:

Bevilacqua, Alexander. “The Qur’an Translations of Marracci and Sale.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 76, no. 1 (2013): 93–130. https://doi.org/10.1086/JWCI24395514.

Dearman, J. Andrew. “EDWARD ROBINSON: Scholar and Presbyterian Educator.” American Presbyterians 69, no. 3 (1991): 163–74.

Kidd, Thomas S. American Christians and Islam : Evangelical Culture and Muslims from the Colonial Period to the Age of Terrorism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691186191.

Murre-van den Berg, Heleen. “WILLIAM MCCLURE THOMSON’S THE LAND AND THE BOOK (1859): PILGRIMAGE AND MISSION IN PALESTINE.” New Faith in Ancient Lands, 32:43–63. United States: BRILL, 2006.

Obenzinger, Hilton. “Americans in the Holy Land, Israel, and Palestine.” In The Cambridge Companion to American Travel Writing, 145–64. Cambridge University Press, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL9780521861090.009.

Obenzinger, Hilton. American Palestine: Melville, Twain, and the Holy Land Mania. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1999.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. 25th Anniversary edition / with a new preface by the author. New York: Vintage Books, 2003.

Sherrard, Broke. “‘Palestine Sits in Sackcloth and Ashes’: Reading Mark Twain’s The Innocents Abroad as a Protestant Holy Land Narrative.” Religion and the Arts (Chestnut Hill, Mass.) 15, no. 1–2 (2011): 82–110. https://doi.org/10.1163/156852911X547484.

Vogel, Lester Irwin. To see a promised land: Americans and the holy land in the nineteenth century. University Park, PA, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993.

Williams, Jay. “The Times and Life of Edward Robinson.” The Bible and Interpretation, May 2003. https://bibleinterp.arizona.edu/articles/robinson#:~:text=Although%20there%20had%20been%20many,Land%20as%20his%20primary%20aim.