I had major FoMO 1 when doing my research on Boon Tan. According to Wesleying, a humor blog at Wesleyan––Boon Tan, this little guy on the right, was “the most infamous pre-Internet meme Wesleyan had yet known back in the ’70s.”2 In 1990, a 10-year reunion T-shirt of the Class of 1980 asked, “Where is Boon Tan?”

But wait… before caring about where Boon Tan is, I had a million other questions. To start with––who, or what even is Boon Tan? And WHY is Boon Tan?

1. What is Boon Tan? Evil Incarnate, Weird Wes, and Vandalism

Before you start lecturing me, I know FoMO is unhealthy. But come on––we’ve all been there. As a first-year student at Wesleyan, wouldn’t you want to learn more about your own campus culture so that you could feel like you’re part of it?

So I met up with our very own University Archivist Amanda Nelson, hoping to find some answers in the stacks of Olin Library’s Special collections & Archives.

It turned out that I was not the only one FoMO-ing about Boon Tan; Steve Blum ’81 shared my wannabe-Indiana Jones curiosity and even wrote a whole essay about the lore of Boon Tan on Wesleyan’s campus. Blum noted the proliferation of Boon Tan symbols in the tunnels of the Butterfield and West College Dorms, the staircase and basement of Science Library, and on the school newspaper, The Wesleyan Argus.5

Kudos to him––Blum replicated 12 pages’ worth of graffiti he’d found across campus, as you can see from the file below.

Indeed, Blum was a very hardworking student, and the Wesleyan students of his time did not fail to demonstrate our top-notch creativity.

Apparently, according to a 1984 Argus article, Boon Tan was “the god of evil,” “a symbol of hedonistic acts,” and “a malevolent spirit.”6 He is, quite simply, the evil incarnate, associated with puns like “SA-TAN,” “BOMB TAN,” and “FRANKEN-TAN.”

If you are a Wes alumni reading this, I regret to tell you that the tunnels Blum went to are, unfortunately, closed to students now. If you are a current student reading this, you may find the photos below helpful in visualizing where these graffiti were (or perhaps, still are) located. If you have sharp eyesight, I also have a challenge for you––spot the iconic Boon tan symbol in the two pictures!

In his essay, Blum highlighted Boon Tan’s cultural significance on campus, as students shared “a certain pride in their intimate knowledge of the lore”:

The Boon Tan lore helps people form a sense of identity and belonging. This is especially important to freshpeople. The introduction to Boon Tan forms a kind of rite of initiation; it marks passage into the community of Wesleyan. It helps establish ties and connections between a group of strangers who have been brought together from all over the country. Boon Tan can be an important “thing in common” among people… on a socially fragmented, physically spread out and politically divided campus.

Steve Blum ’81, “Folklore Project,” April 19, 1980

See? Blum agreed with me on Boon Tan’s particular importance to first-year students. As an inside joke, it forged a sense of community, allowing students to build collective memory around it––according to Halbwachs’ theory.9 Blum also rightly pointed out that to stressful Wesleyan students, Boon Tan brought “a feeling of pleasure and enjoyment to those who read it as well as those who put it up” and functioned as an entertaining “study break.”

Indeed, within the social structure of a college, the rituals of both reproducing the Boon face symbol creatively and visiting past graffiti in hidden places were incorporated into institutional traditions. In simpler words, Boon Tan was the big thing on campus.

Even after all these years, in the comment section of Wesleyan’s official Facebook account, alumni still bonded over the shared memory of Boon Tan, as seen in the screenshot on the left.

If I were a first-year back in Blum’s time, I would without a doubt have left a drawing or two behind, rebelliously vandalizing public property. (Rest in peace, the tunnels!) Blum emphasized the pressure Wesleyan students faced “to exercise their individualism and somehow be different from everyone else.” I’m surprised this has not changed after so many years.

After all, Boon Tan perfectly encapsulated the unique Wesleyan identity, where all of us want to be seen as eclectic, edgy, funny, and alternative. Actually, Wesleyan students want to be seen as MORE eclectic, MORE edgy, MORE funny, and MORE alternative than others.

Boon Tan perfectly resonated with Wesleyan students’ desire for validation of their quirkiness, which has been so integral to the Wesleyan spirit that when it seemed to be threatened by the administration’s certain initiatives, alumni across industries joined hands to start a movement called #KeepWesWeird.

And quite literally, Wesleyan students competed to see who could create the best Boon Tan meme. In 1982, there was an actual contest in The Wesleyan Argus to come up with Boon Tan jokes.

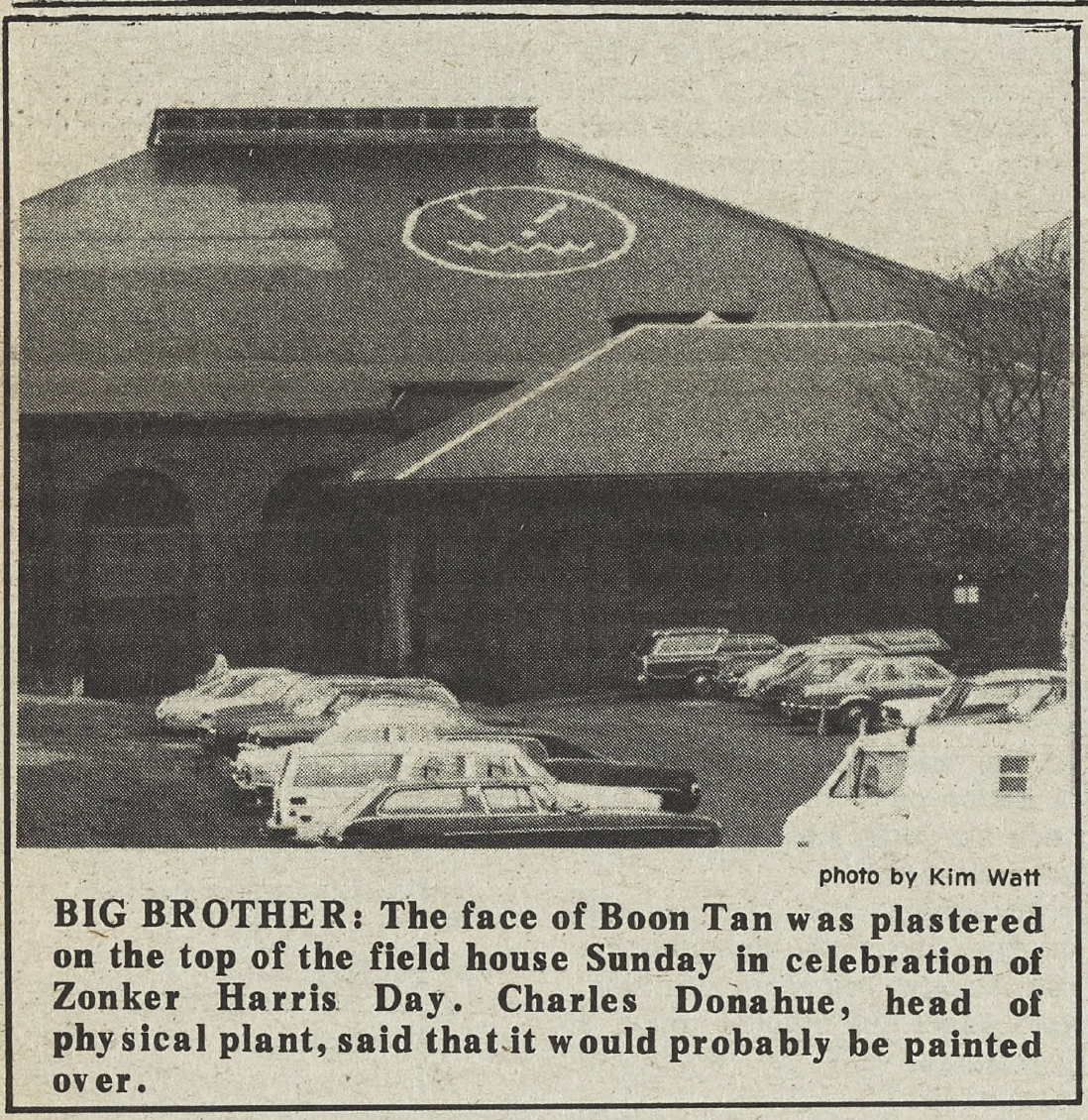

Some students went a bit further. In 1977, to celebrate Zonker Harris Day, another campus tradition, someone put up a giant Boon Tan face on top of the Field House, where Usdan University Center currently stands. It is believed to be the largest display until today. A similarly public display was made in 2008, when an anonymous person created and pictured Boon Tan in the courtyard of the Butterfield Dorms.

As the new generations of Cardinals, I’m sure you all are as creative as some of our alumni. Let’s all try creating a pun with Boon Tan’s name in it14:

Loading…A testament to Boon Tan as a global phenomenon, there were also reports about Boon Tan sightings from all over the world. The symbol was found in Stamford, CT, over New York subways, and even in a canal in Venice, Italy.

There are a few places that you are guaranteed to meet him: The University of Chicago Library system, Chinatown in both San Francisco and New York (“Boon hopes you piss on your leg”), above the waterline in a canal in Venice (“Sink and rot”), and the men’s room in the Louvre in Paris.

Marc Rosner ’86, writing for The Wesleyan Argus, Nov. 9, 19846

I would love to know who drew the Boon Tan likeness in the second-floor men’s room at American Cyanamid’s Stamford research laboratories!

Dennis J. Jakiela ’78, in a note to the Wesleyan Alumni Magazine, Winter 199115

About 1979… I saw Boon Tan all over the New York subway (in those days it was covered in graffiti––I understand it’s clean now). It even appeared on two sides of a lift door in a building down in the village, which closed to reveal evil in all its glory.

Tod Norman ’79, in an email to Wesleying, May 20082

But the question remains–––who is Boon Tan?

Blogging While Feminist, another alumni blogger, said she “seemed to remember an allusion to Boon Tan in an episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer,”16 a popular TV show created by Joss Whedon ’87. Needless to say, it is another example of Boon Tan’s ubiquity. After reading her blog and watching Buffy (the Vampires know how much time I spent on this article!), I think I can finally piece together Boon Tan’s story. And guess what? He was played by no other than Pedro Pascal.

2. Who is Boon Tan? Pedro Pascal, Luggages, and Malaysia

tl;dr 17: Boon Tan was a student at Wesleyan who never showed up. End of the story––thanks for reading my article!

Unless... you want to see young Pedro Pascal? Then bear with me.

In the fall of 1976, Boon Tan was supposed to come to Wesleyan and live in Foss Hill, Unit 4. Boon didn’t show up during orientation. Word was that he would be coming during the first week of classes. He didn’t. By the second week of classes, he wasn’t there, but [others] started to play jokes on Boon’s erstwhile roommate… They would leave suitcases outside the room with notes saying Boon was at dinner. Or they would call up and say they were Boon. Amidst the frivolity, someone asserted that Boon had planned this all along, to undermine [his roommate]. So, the seed of Boon as an evil spirit was planted.

David Oppenheimer ’78, then-head of West College, in an email to Blogging While Feminist 18

If you are bored of words, Pedro Pascal in the video below will enact a similar story. He played Eddie in Season 4, Episode 1 of Buffy, whose character I believe was at least partially inspired by Boon Tan.

Back to the real life story. Oppenheimer first drew the Boon Tan face to make a female resident feel safe. But the symbol soon got immensely popular and was reproduced across campus, with Boon Tan’s legend becoming a mystery. Differing theories began to spread about his country of origin, his reason for not coming to Wesleyan, and where he actually ended up. Some people said his luggages were here, or he showed up for a bit, but at least according to Oppenheimer, those was merely pranks by his hall-mates.

But––apologies for asking this question the millionth time but none of the sources seemed to have answered me––who actually is Boon Tan?

Eventually, I dug out an official yearbook that offered some hope. The yearbook, dubbed “face book” in its most original meaning, records Boon Tan’s full name and hometown, while also featuring a photo of his. After all these arduous attempts, finally, Boon Tan is not a symbol, not a curse, but a human being again! Yay!

The face book clearly shows that student Boon C. Tan is from Province Wellesley, Malaysia, something easily verifiable that still confused many students, including Blum and several Argus writers and interviewees. In case you also didn’t know, Malaysia is a country located in Southeast Asia, as visualized by the globe on the right.

On the left is also a map of the Western part of Malaysia––with Boon Tan’s hometown, Province Wellesley (now Seberang Perai), marked red.

Interestingly, Province Wellesley was renamed with an Malay name around Malaysia’s independence in the 1960s,23 yet the official record of Wesleyan still relied on the colonial-era term. Practically and understandably, it might be because the old name was easier to spell and pronounce. But even then, I’d like to ask: why must English be the standard?

I want to assert that, in a university that obviously was trying to diversify its student population (by enrolling a Malaysian student), insisting on the properness of English could be an inherently flawed ideology and a new form of colonialism erasing minority identities.

Another fun bit if you look at Boon Tan as a person but not a meme: Boon’s surname, Tan, is till this day the most common surname in Malaysia, held by descendants of Southeast Chinese immigrants. It’s a romanization from 陳 in Hokkien dialect, spoken in Southeastern China.24

If you have any Chinese friends, you may realize that some of them, also surnamed 陳, may have a different romanization––such as Chen, Chan, or Tham.25 The truth is, under colonial rule, the transliteration of Chinese names in Malaysia was entirely up to the discretion of British officials, who followed English phonetics.27 And because different dialects have slight differences in pronunciation, they resulted in drastically different spellings even though they might be from the same family branch.

I hope you liked my Malaysian History 101. Years ago, in mocking Boon Tan, Wesleyan students’ confusion with Asian countries in my opinion not only suggests unfamiliarity but more importantly underscores their unwillingness to learn.

Indeed, many of the puns around Boon Tan referenced Japanese, Mongolian, Vietnamese, and Indian histories/cultures that have nothing to do with the original figure himself. Some of them poke fun at historical trauma of Asian communities, such as “Atomic Boon” and “Big Brother Boon;” others could be read as orientalist, fetishizing exotic components of Asian customs, such as the case of “Tofu Tan;” and almost all of them indicate that students viewed Asia — the largest and most populous continent on earth — as uniform.

It’s now time to talk about the most difficult question of it all––what was the fun all about?

3. Why is Boon Tan? Makeup, Yellow Peril, and the PCU

Let’s take a short break before delving further. I have a little quiz for you:

What do you think? At least when I sent the poll around to my friends, most chose the actor on the left. But were they right?

–––––––––––––––––––

WARNING: SPOILERS AHEAD! Only proceed after you’ve picked your own answer.

Unfortunately, only the actor on the right28 has Asian heritage. Her name is Phillipa Soo; she is of half-Chinese descent.29 She was famously known for playing the role of Eliza Hamilton in the musical Hamilton on Broadway, created by Lin-Manuel Miranda ’02.

The actor on the left29 is Mickey Rooney, a White actor, portraying Holly Golightly’s Japanese neighbor in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” (1961).

Naturally, all of my friends asked, “But why did he look so Asian?”

To address that question, I’d like to pose a new one: what does being Asian look like?

I asked AI to draw an Asian guy for me. To the right is what cutout.pro gave me.

To AI, a makeup artists in Hollywood, the answer seems simple: slit eyes.

Fueled by general Sinophobia,30 Hollywood producers were reluctant to cast Asian actors.31 Therefore, there has been a long history of makeup artists drawing slanted eyes to transform White actors into villainous Asian characters.32

Here is a more in-depth video explaining Hollywood’s troubled history with Asian characters.

Admitted to a selective liberal arts college, Boon Tan was clearly smart. Calling him “evil incarnate” could have been a reference to Fu Manchu, the archetype of the evil Asian genius.35 Introduced in by the English author Sax Rohmer, Fu quickly became a racist stereotype of the Asian mad scientist and supervillain. A side-by-side comparison of Christopher Lee (White) as Fu Manchu and an Argus article clearly shows that some of the art around Boon Tan was directly alluding to the Fu Manchu character.

At the core of it all, the characterization of slant-eyed Asians as evil alludes to the Yellow Peril, whereby people from East and Southeast Asia are seen as a danger to Western society.37

Steve Englehart ’69, creator of Shang-Chi in the Marvel Comics and our very own alumnus, recounted to The Wesleyan Connection the resistance his team faced in creating the Asian superhero in an interview.38

“[Marvel] imposed on us [that Shang-Chi] had to be half-white… and they came up with the idea of making his father Fu Manchu.”

Steve Englehart ’69, in an interview with The Wesleyan Connection

date unknown.39

I also found a piece of flyer advertising an “Oriental Sale” on Washington St. in Middletown, CT. Not surprisingly, it also relied on the same slanted-eyed archetype to denote Asianness.

But the blatant racism of Boon Tan did not go unnoticed. A few professors of Asian Studies, as well as Asian student groups, penned Letters to the Editor to The Argus resenting the Boon Tan joke and the newspaper’s coverage.

Notably, Professors of Asian Languages and Literatures Yoshiko Yokochi Samuel and Anthony Chambers both wrote to The Argus to protest the aforementioned “This is Boon Tan” article.

Similarly, Asian student groups would not stay silent at the hate they encountered on a daily basis.

We live unjustly under the evil stereotyped epithets such as “Gook,” “Chink,” “Nip,” “Oriental Jew,” and “Yellow Nigger.”

Wesleyan Asian Students Party, Writing to The Wesleyan Argus, April 19, 1974.42

Ethnocentricity is a far worse enemy than overt racism, for it… perpetuates ignorance, fear, and all of the attending mythic misconceptions that white America harbors against the third world, albeit at an unconscious or unspoken level.

Steven Hata ’74, Writing to The Wesleyan Argus, April 19, 1974.43

But what makes the prevalence of jokes like Boon Tan especially concerning is the context in which they had found an audience: Wesleyan, which has long been known as the “politically-correct university” (and inspired two alums to create a movie titled “PCU”44). It is supposed to be liberal, progressive, and inclusive, with a student population of "social justice warriors" who champion equality. What is with the double standard when it comes to racist portrayals of Boon Tan?

Here, I argue that it is the two sides of the same coin. Jokes like Boon Tan portray Asians as monstrous dangers; while the university—with its superficial progressiveness––also won’t shut up about how much they celebrate the extraordinary resilience that we students of color have gained when struggling with all of our identities. Our monstrosity is shunned away; our ethnicity is fetishized.

White liberals on my own college campus enjoy performing pity towards folks of color, enacting a modern version of “The White Man’s Burden.”45 I myself, a Freeman Asian Scholar, am here because of the campus' commitment to a fancy term called “internationalization.”46 Quite frankly speaking, I'm here as an exhibit for diversity.

I’d like to draw you attention to the admissions brochures pictured below, which featured Asian/Asian-American students, produced in the 1990s––around the same time when Boon Tan was still a popular meme, and when multiple racist incidents were reported in The Argus.47

Just as we are dehumanized into evil genius archetypes, the challenges we face as ethnic minorities are also exploited as marketing material––we are reduced to and trapped in a confusing series of dehumanizing acronyms like “AAPI,” “BIPOC,” and “FGLI.”51

Perhaps, just as Hiram Perez notes, “White folks performed the intellectual labor while black and brown folks just plain performed.”52

In the competition for individualism that Blum noted amongst Wesleyan students, I find that my peers, generally from more privileged backgrounds, can be self-congratulatory in seeming progressive and cool. Ella Dawson ’14 called this “a competitive culture of activism that can feel more performative than genuine.”53

Wesleyan students tear at each other out of fear, desperate to be the most woke because that means validation and fame.

Ella Dawson ’14, writing in her personal blog

Ultimately, in the dichotomy of threat/treasure, ignorance/fetish, evil/saintly, we are treated either as non-humans or as super-humans. But never could we ever just be normal, basic humans.

4. Seeing the Human

To conclude, let’s go back to the 1984 Argus article,6 which also mentioned Kok Peng Chong, a Malaysian friend of Boon Tan:

Kok Peng Chong, [who] also went to Bukit Mertajam High, [was] accepted to Wesleyan a year after Boon, [and] was friends with Boon, … [was] mostly confused about the whole thing. He knew Boon wasn’t a malevolent theme but felt that it was somewhat racist.

Marc Rosner ’86, quoting David Oppenheimer ’78, The Wesleyan Argus, Nov. 9, 1984

But Kok was not even directly quoted but was indirectly brought up by Oppenheimer––who went under the pseudonym of Mike Stern in the article.

It seems that even the most basic personhood of Asian students were casually ignored.

How do we navigate the incompatibility between students’ ostensible progressiveness and their ignorance of cultures and peoples different from their own? My answer is simple––just treat them as people, not stereotypical villains nor token selling points for inclusivity.

Just people.

To do this, we have a long line of pioneers to look up to. While curating this exhibition, I was able to get in touch with Peng Khuan Fong ’73. Fong shared the history of the aforementioned Wesleyan Asian Students Party, which he co-founded with a few other Asian students who felt strongly about being stereotyped on campus since the 1970s. The group's acronym, WASP, was a wordplay on its conventional meaning, which stands for “White Anglo-Saxon Protestant.”

As Fong pointed out, the Boon Tan saga exposed “the deeply ingrained racism” that, till this day, continues to exist at Wesleyan, which Fong called “a microcosm of American society that styles itself as neo-liberal and progressive.”54

.... It was an active group during the height of the Vietnam and Indo-China anti-war movement. With funding from the student body, we organized many events to showcase Asian arts, culture, food, history and festivities. We brought in movies, speakers, artistes and so on. For example, we hosted a visiting wayang kulit troupe from Kelantan to perform at Wes to supplement the Javanese gamelan music and dance program. We cooked many sellout Asian meals for interested students at 5 bucks per head to pay for our countless activities.

All these actions were to increase awareness of Asian ways of life, culture and heritage on campus. In a sense, we were trying to combat inherent racism and insensitivities that prevailed.

Peng Khuan Fong ’73

A truly “diverse” and “internationalized” Wesleyan is one where all of us embrace each other’s nuances, complexities, and chaotic energies––also known as, our beautiful humanness.

Notes & Bibliography

Notes

1. FoMO: “Fear of Missing Out.”

17. tl;dr: “too long; don’t read.”

51. AAPI: “Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders”; BIPOC: “Black, Indigenous and people of color”; FGLI: “first-generation, lower-income” students.

Primary Sources

Physical Sources (from Special Archives & Collections):

3. Class of 1980 Alumni 10-Year Reunion T-shirt, May 1990.

5. Steven Blum ’81, “Folklore Project,” April 19, 1980.

6. Marc Rosner ’86, “THIS IS BOON TAN,” The Wesleyan Argus, November 9, 1984.

7. Photo by Liz Shulman ’99. The Wesleyan Argus, February 6, 1995.

8. Photo by Randy O’Rourke. Connecticut magazine, October 1987.

11. “Boon Tan” Recreation Contest, The Wesleyan Argus, May 7, 1982.

12. Photo by Kim Watt ’87. The Wesleyan Argus, May 3, 1977.

15. Wesleyan Alumni Magazine, Winter 1991.

20. Class of 1979 freshman face book, Fall 1976.

39. “Oriental Sale” Advertisement, Custom Carpets, n.d.

40. Yoshiko Yokochi Samuel, “Letters to the Editor,” The Wesleyan Argus, November 14, 1984.

41. Anthony Chambers, “Letters to the Editor,” The Wesleyan Argus, November 19, 1984.

42. Wesleyan Asian Students Party, “Letter to the Editor,” The Wesleyan Argus, April 19, 1974.

43. Steven Hata ’74, “Wes Gives Asian Americans Much Cause To be Unhappy,” The Wesleyan Argus, April 19, 1974.

47. Yau-mu Mike Huang ’92, “I’m Sorry, It Was Only a Joke,” The Wesleyan Argus, May 3, 1991.

48, 49, 50. Office of Admission, “Asian/Asian-American Students at Wesleyan” Brochure, 1993-1995.

Interview:

54. Peng Khuan Fong ’73, via email, May 2023.

Digital Sources (from the Internet):

2. Ashik Siddique ’10, “Remember the Boon!”, May 13, 2008. http://wesleying.org/2008/05/13/remember-the-boon/.

4. Original adaptation on May 20, 2023, based on screenshots from “Avengers: Infinity War,” Marvel Studios, 2019. https://sports.yahoo.com/22-unscripted-marvel-scenes-actors-024602153.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAGX44i8TgHrjrC8XPuMkqjYtlToq9s5Ub19-fWSYak8HvfXsEQhS99_DhjsPBsB0UXgVnKdd3JkKn8ncixHhb0-e74jnFqsC0S6uwnAL3C8PI7YTtyh3vE2hgurb1r8tmF9hSsqihMtJ9q4cVu0iCjHOqZDeeFEodWmNUj0BpmeA.

10. Wesleyan University, “#TBT What do you know about the (now closed) Butterfield tunnels?”, Facebook, November 9, 2017. https://www.facebook.com/wesleyan.university/posts/tbt-what-do-you-know-about-the-now-closed-butterfield-tunnels-built-in-1965-the-/10150920261124995/.

13. Photo by anonymous. Wesleying, May 14, 2008. http://wesleying.org/2008/05/14/rise-and-shine-boon-tans-outside-your-window/.

14. Original interactive feature, created on Super Survey, May 20, 2023. https://qs3g5yner.supersurvey.com.

16. “The Legend of Boon Tan.” Blogging While Feminist, April 18, 2006. http://plainsfeminist.blogspot.com/2006/04/legend-of-boon-tan.html.

18. “Behind the Wesleyan Legend: Boon Tan, Part Two.” Blogging While Feminist, August 7, 2006. http://plainsfeminist.blogspot.com/2006/08/behind-wesleyan-legend-boon-tan-part.html.

19. January Media, “Eddie The Freshman: Who Is Pedro Pascal In Buffy The Vampire Slayer? 😍”, YouTube, March 21, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8ewOP-R2LGE.

21. GISGeography, “Malaysia Map,” GISGeography, October 31, 2022. https://gisgeography.com/malaysia-map/.

22. Dreamtrooper, “Seberang Perai in Penang and West Malaysia Map,” Wikipedia, April 29, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seberang_Perai#/media/File:Seberang_Perai_in_Penang_and_West_Malaysia_map.png.

26. Original image, April 20, 2023.

28. Photo by Jordan Geiger for Rose & Ivy, August 10. 2020. https://www.roseandivyjournal.com/stories/2020/8/5/mornings-with-phillipa-soo-star-of-hamilton. Poll created from Poll Maker on May 20, 2023. https://linkto.run/p/BS1PFDAL.

29. Screenshot from “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” Paramount Pictures, 1961. https://www.sutori.com/en/item/late-famous-actor-mickey-rooney-portrayed-stereotyped-japanese-character-mr-yu. Poll created from Poll Maker on May 20, 2023. https://linkto.run/p/BS1PFDAL.

33. Original AI-generated image, “AI Art Generation,” cutout.pro, accessed May 20, 2023. https://www.cutout.pro/ai-art-generation/upload.

34. Vox, “Yellowface is a bad look, Hollywood,” YouTube, April 21, 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zB0lrSebyng.

35. Sax Rohmer, Fu-Manchu: The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu, (London: Titan, 2012).

36. Still from “The Face of Fu Manchu,” Hammer Film Productions, 1965. https://pixels.com/featured/christopher-lee-in-the-face-of-fu-manchu-1965--album.html.

38. Steve Scarpa, “Englehart ’69 Creator of Newest Marvel Movie Hero,” The Wesleyan Connection, August 16, 2021. https://newsletter.blogs.wesleyan.edu/2021/08/16/englehart-69-creator-of-newest-marvel-movie-hero.

46. Fries Center for Global Studies, “Internationalization,” Wesleyan University, accessed May 20, 2023. https://www.wesleyan.edu/cgs/internationalization/index.html.

Secondary Sources

9. Maurice Halbwachs, On Collective Memory, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1992), trans. from: Les cadres sociaux de la mémoire, (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1952), originally published in Les Travaux de L’Année Sociologique, (Paris: F. Alcan, 1925).

23. Khoo Salma Nasution, Seberang Perai: Sejarah Bergambar = Province Wellesley: A Pictorial History Paperback (Penang, Malaysia: Areca Books, 2016).

24. National Library Singapore, “[We Like It Rare] What’s in a Name?”, Medium, January 6, 2021. https://medium.com/the-national-library-blog/we-like-it-rare-whats-in-a-name-78803a4e7ab9.

25. “Tan Chinese Last Name Facts,” My China Roots, accessed May 20, 2023. https://www.mychinaroots.com/surnames/detail?word=Tan.

27. 彭成毅, “How to Understand the Confusing Spellings of Romanized Chinese Names,” The News Lens, August 30, 2018. https://international.thenewslens.com/article/103065.

30. Sang Kil, “Fearing yellow, imagining white: Media analysis of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882,” Social Identities. 18 (2012): 1-15. doi:10.1080/13504630.2012.708995.

31. Sylvia Shin Huey Chong, “What Was Asian American Cinema?” Cinema Journal 56, no. 3 (2017): 130–35. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44867826.

32. Alicia Lee, “The ‘fox eye’ beauty trend continues to spread online. But critics insist it’s racist,” CNN, August 11, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/style/article/fox-eye-trend-asian-cultural-appropriation-trnd/index.html.

37. Michael Odijie, “The Fear of ‘Yellow Peril’ and the Emergence of European Federalist Movement,” The International History Review. 40 (2) (2018): 359. doi:10.1080/07075332.2017.1329751.

44. Eric Ducker, “The Oral History of ‘PCU’, the Culture Wars Cult Classic,” Vice, April 5, 2022. https://www.vice.com/en/article/xgd3yz/pcu-movie-oral-history-culture-wars-cult-classic.

45. Rudyard Kipling, “The White Man’s Burden: The United States & The Philippine Islands, 1899.” Rudyard Kipling’s Verse: Definitive Edition (Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday, 1929).

52. Hiram Perez, “You Can Have My Brown Body and Eat It, Too!,” Social Text 23, no. 3-4 (84-85) (December 1, 2005): 171–91, doi: 10.1215/01642472-23-3-4_84-85-171.

53. Ella Dawson, “Five Years Later, Wesleyan Is Still The Best Decision I’ve Ever Made,” Ella Dawson, May 28, 2019. https://elladawson.com/2019/05/27/five-years-later-wesleyan-is-still-the-best-decision-ive-ever-made/.

About the author:

Sida is a Freeman Asian Scholar at Wesleyan University. A trans writer and theater-maker, she enjoys black coffee, corny rom-coms, and anything matcha-flavored. She’s always curious about the problematic opposites of history and myth, page and stage, theology and biology, East and West, yin and yang, women and men—and everything in between and beyond.