When the Canary Falls Silent: An Introduction to Asian American Studies Organizing at Wesleyan

Students have advocated for the creation of an Asian American Studies program at Wesleyan since the 1980s. This exhibit draws on available materials in the Wesleyan archives—primarily articles and Letters to the Editors from The Argus—to follow the various movements for AsAm Studies across these four decades. It begins with the emergence of self-taught student forums in 1985 and then turns to the work of multiple organizations, including the Wesleyan Asian/Asian American Student Union (WA/AASU), the Student of Color Council (SCC), the Asian/Pacific American Alliance (APAA), and the presently active Asian American Studies Working Group (AASWG). In tracing these students’ efforts, a larger historical pattern reveals itself: a serious lack of administrative support for AsAm Studies. Pushes for AsAm studies have been met with little institutional response, and with only four years or fewer on campus, multiple generations of student leaders struggled to pass down their institutional knowledge and ensure their work would be taken up by younger students. This results in a continuing state of institutionalized disregard for AsAm Studies.

As Wesleyan students continue to advocate for Asian American Studies today, this exhibit highlights Asian American students’ lasting commitment to such a program and grounds their efforts in 30+ years of organizing history. Furthermore, by identifying institutional disregard as the University’s recurring response to calls for AsAm Studies, this exhibit directly challenges the kind of forgetting that limits a movement within a student’s four years at Wesleyan. It may also serve as a resource to future students for developing new strategies to build AsAm Studies.

Why Asian American Studies?

In 1968, UC Berkeley student activists Emma Gee and Yuki Ichioka coined the term “Asian American,” seeking to build solidarity across communities of Asian descent. Asian American Studies is an academic field that expands upon Gee and Ichioka’s vision for a pan-ethnic racial politics, examining the experiences of Asians in America through histories of labor, migration, colonialism, imperialism, citizenship, and nationality. Because of the wide range of ethnicities, immigration histories, class backgrounds, and experiences that fall under the “Asian American experience,” Asian American identity is something that people continue to construct, revise, critique, and rebuild. Being Asian American does not automatically impart comprehensive knowledge of Asian American history, culture, and politics. Thus, Asian American Studies is not only a lively, interdisciplinary academic field, but also functions as a critical site for Asian American students to develop greater consciousness of themselves and their relationships to their communities. Today, the sharp increase in anti-Asian violence linked to the coronavirus pandemic underscores the importance of an academic program devoted to the study of Asians in America.

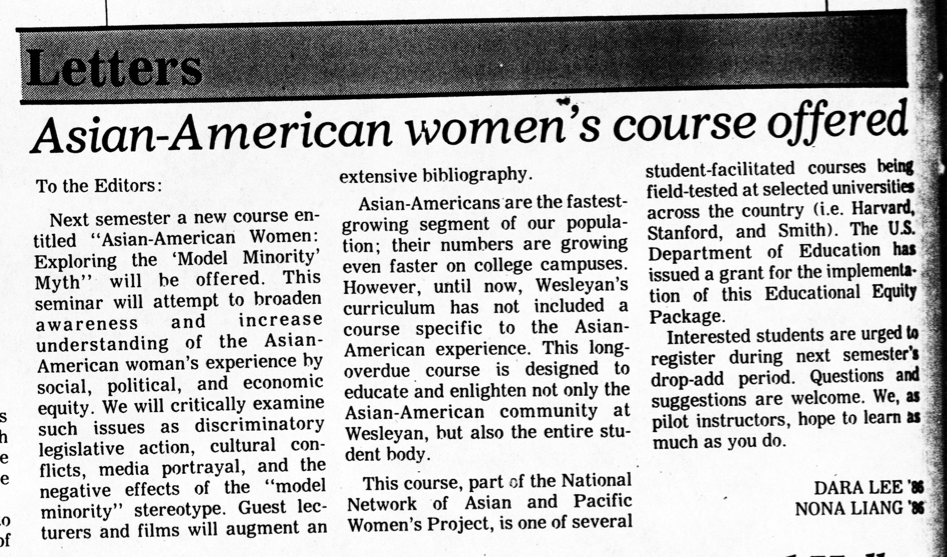

According to the Argus, students began requesting courses in AsAm studies in the early 1980s, and in the spring of 1986, seniors Dara Lee ’86 and Nona Liang ’86 taught a student forum titled “Asian-American Women: Exploring the ‘Model Minority Myth.’” For two more years, student teaching assistants continued to teach tutorials focusing on various aspects of Asian American Studies each semester. Students recognized the limits of student-taught tutorials: teaching assistants had to find their own course materials and create their own syllabi with neither the scholarly training of a professor nor a career’s worth of teaching experience. Furthermore, the Educational Policy Committee ruled that student-run tutorials were not worthy of Wesleyan credit. The tutorial was also growing increasingly popular; by the spring of 1989, the tutorial split into two sections with four teaching assistants.

After countless meetings with faculty, administrators, and students over five years, leaders of the Wesleyan Asian/Asian-American Student Union (WA/AASU) finally brought Wesleyan’s first Asian American Studies class to campus in the spring of 1990—Asian-American History and Culture taught by Visiting Professor Grace Yun.

However, after running for one semester, Eveline Wu ’93 published a letter to the editors on behalf of WA/AASU informing the Wesleyan community that Professor Yun’s class had been canceled. “We are upset that our efforts to maintain a regular, yearly course on Asian American historical experience has again been met through haphazard last minute arrangements,” Wu wrote. “The class has been neglected and the Wesleyan student body has not even been informed of its cancellation.” A later Argus article notes that two hundred students showed up for the first day of the forty-person class. Still, no explanation for the course’s cancellation was offered.

The following year, the Students of Color Council (SCC) published a Wespeak article titled “Asian American and Latino Studies Suffer at Creighton’s Hands.” After conducting a year of research into avenues of inclusion for Asian American and Latino studies in Wesleyan’s curriculum, SCC had submitted a proposal on April 10, 1992, to President Joanne Creighton. The proposal requested that, for the next three years, a fund of $15,000 per year be dedicated to support course offerings in Asian American and Latino studies until “more permanent options can be explored with the faculty.” President Creighton denied the request. In her discussion of AsAm Studies specifically, she wrote, “I am pleased to note that we have hired four Asian Americans this year.” In response, SCC observed that none of the four Asian American faculty members Creighton had referred to were even trained in AsAm Studies.

“All this work and they were still getting nowhere. Each time there seemed to be a small success for the student organizers, the mechanisms of university politics would dramatically diminish its importance… Students can only do so much in impressing their ideas upon administrators who undeniably always have the final say in academic programming.”

Notes of a Frustrated Ethnic Studies Activist by Ussuri Yu ’99

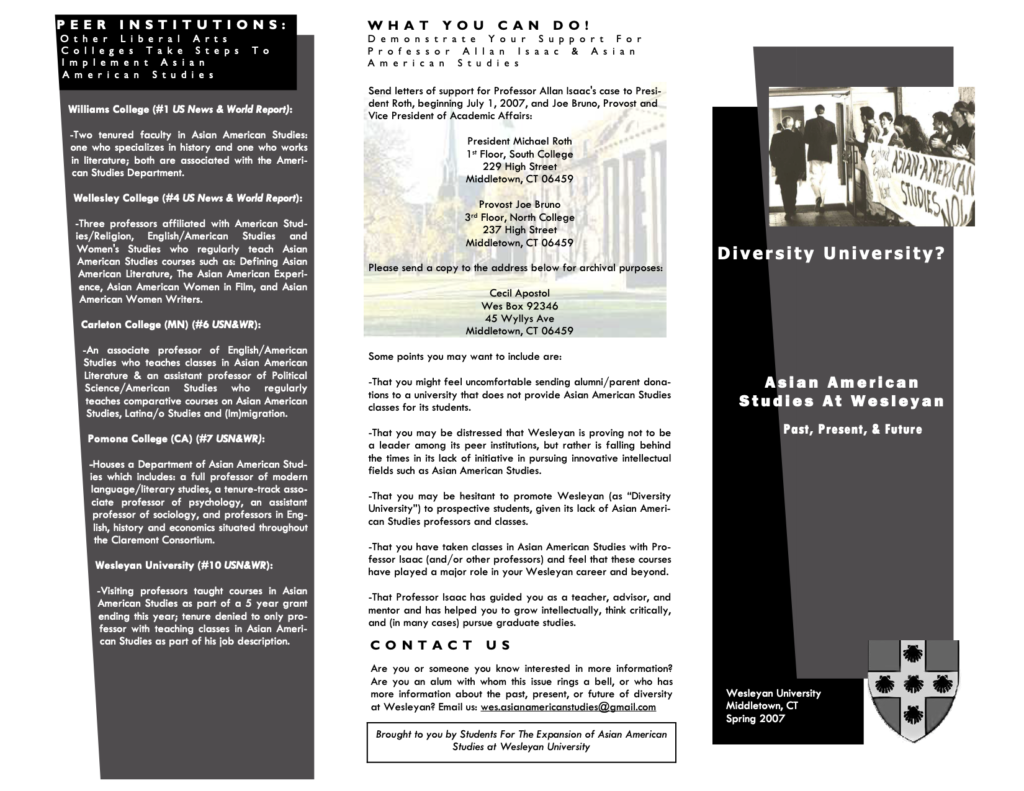

In the spring of 2007, the only Wesleyan professor consistently teaching courses in Asian American studies— Allan Punzalan Isaac—was denied tenure. This coincided with the end of the Freeman Asian/Asian American Initiative, a five-year grant that brought Asian American studies scholars to campus for teaching and research residencies, funded multiple student summer research projects in Asia, and sponsored lectures, performances, and workshops on campus.

Students recognized Isaac’s departure as the loss of a brilliant scholar and beloved mentor. Furthermore, they saw that the denial of tenure to Isaac was a significant blow to efforts to institutionalize Asian American studies at Wesleyan. Various classes in the field had been offered since 1990, yet without an academic home in the form of a major, department, college, or program, they were taught at the discretion of current faculty—none of whom, with the exception of Professor Isaac, had Asian American Studies in their job description. In response, students demanded that the tenure decision be reversed. They protested throughout campus, conducted a letter campaign to incoming president Michael Roth, and circulated a pamphlet and petition signed by hundreds of members of the Wesleyan community. Later that spring, over one hundred graduating students wore “Tenure Isaac” patches on their gowns at commencement.

Asian American Studies at Wesleyan Today

There is no major, minor, certificate, college, or program in AsAm Studies at Wesleyan. Existing courses in the field are offered at the discretion of faculty and are listed under the “Asian American Studies Cluster” on WesMaps, which allows students to find classes that fall under AsAm Studies listed together on a single webpage. According to the cluster website, there will be three fall courses and four spring courses offered in the 2023-2024 school year, but the existence of the cluster does not guarantee that AsAm Studies classes will be offered in future years. For example, “HIST259: Asians and Pacific Islanders in U.S. Empire” will not be taught next semester, meaning that there are no classes in Asian American history next year. Thus, while the cluster creates a convenient way for students to view what courses in Asian American studies are offered, it does not guarantee that they will continue to run in future semesters. Furthermore, existing courses primarily fall under the English, American Studies, Religion, History, and College of East Asian Studies departments. As AsAm Studies is an interdisciplinary field, offerings in other disciplines (including sociology, political science, and psychology) would contribute to a more robust program at Wesleyan.

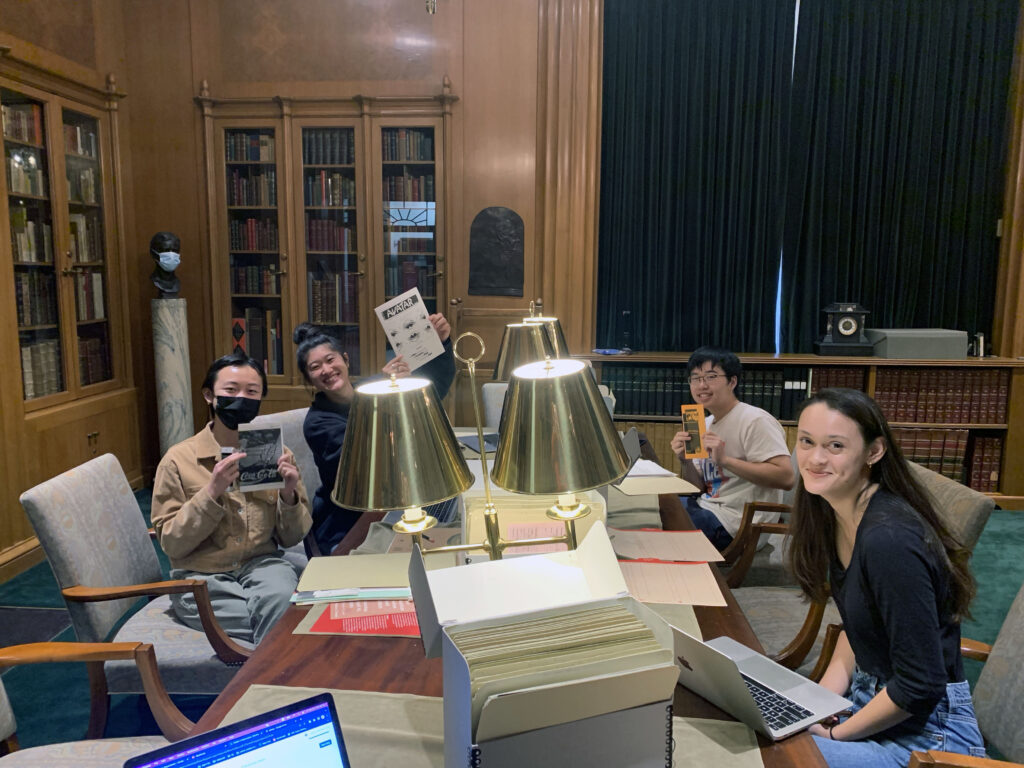

In the spring of 2022, Emily Chen ‘23 and I organized a open meeting for Asian and Asian-American students seeking support and community in the wake of multiple acts of anti-Asian violence, including the deaths of Michelle Alyssa Go, Christina Yuna Lee, and Guiying Ma. During the conversation, many students wondered why they faced silence in their various circles on this subject. In voicing these experiences, the group collectively identified two absences: Asian American community in which to seek emotional support, and academic spaces that provided historical context and analysis of such anti-Asian violence. From these realizations emerged the Asian American Studies Working Group (AASWG).

In October 2022, President Michael Roth made an open call for proposals for the University’s ten-year strategic plan, Towards Wesleyan’s Bicentennial. He invited members of the Wesleyan community to submit 1-3 page long proposals for new programs, majors, and initiatives that would fulfill the three overarching goals of the plan: to “enhance [Wesleyan’s] distinctive educational curriculum,” “build on [its] reputation as a leader in pragmatic liberal education,” and “increase access and sustainability.” The Bicentennial website states that an advisory committee of faculty, staff, and students would conduct initial reviews of all submitted proposals by January 31st, after which selected proposals would move to a second round. In December, AASWG submitted the following proposal outlining next steps in establishing an institutional home for AsAm Studies at Wesleyan.

According to the website, the advisory committee would complete its initial proposal review by the end of January, yet AASWG did not receive any updates regarding the proposal until February 17, when the group received an email from President Michael Roth. After thanking AASWG for its submission, he wrote, “It is my understanding that this proposal is already underway and in the hands of the [Educational Policy Committee] and I look forward to seeing what the faculty decide to do with this proposal. Sincerely, Michael.”

Through multiple conversations with a member of the Educational Policy Committee (EPC), AASWG discovered that their proposal has yet to be formally discussed in the committee, which hosted its last meeting of the 2022-2023 school year on May 15. As of May 20, AASWG has not received any formal updates or communication regarding the proposal since President Roth’s email. Yet contextualized in Professor Yun’s departure, President Creighton’s response to the Students of Color Council proposal, and the denial of tenure to Professor Isaac, perhaps it’s not quite as strange as it appears.

Sources

Primary

Asian American History and Culture Syllabus, Fall 1992, Wesleyan University Hewlett diversity archive, Box 3, Folder 7, Special Collections & Archives, Middletown, CT.

Kang, Juli. “Asian-American Class a First.” The Wesleyan Argus. February 16, 1990.

Lee, Dara, and Liang, Nona. “Asian-American women’s course offered.” The Wesleyan Argus. December 11, 1985.

Page 1 of “Diversity University? Asian American Studies at Wesleyan” pamphlet, 2008-007, Wesleyan University Asian American Student Coalition records, Special Collections & Archives, Middletown, CT.

Roth, Michael. “Open Call for Proposals: Asian American Studies.” Email to Emily Chen, March 17, 2023.

Sachs, Jonah. “APAA Proposes Asian Studies Program.” The Wesleyan Argus. October 25, 1994.

Students of Color Council. “Wespeak: Asian American and Latino Studies Suffer at Creighton’s Hands.” The Wesleyan Argus. May 6, 1992.

“Tenure Isaac & AAS” photos, May 24, 2007, 2008-007, Wesleyan University Asian American Student Coalition records, Special Collections & Archives, Middletown, CT.

“Notes of a Frustrated Ethnic Studies Activist” by Ussuri Yu ’99 in Betel Nut, Spring 2000, Wesleyan University Hewlett diversity archive, Box 3, Folder 7, Special Collections & Archives, Middletown, CT.

Wu, Eveline. “Wesleyan Neglects Asian American Studies.” The Wesleyan Argus. November 15, 1991.

Secondary

Chang, Jason Oliver. “Walking with Asian American Studies.” Journal of Asian American Studies 23, no. 3 (2020): 329–33. https://doi.org/10.1353/jaas.2020.0026.

Cheng, Cindy I-Fen. The Routledge Handbook of Asian American Studies. [Enhanced Credo edition]. New York: Routledge, 2017. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315817514.

Nguyen, Viet Thanh, and Cathy Schlund-Vials. Flashpoints for Asian American Studies. Edited by Cathy Schlund-Vials. First edition. New York, NY: Fordham University Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780823278633.

Okihiro, Gary Y. Third World Studies : Theorizing Liberation. Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

Park, Josephine Nock-Hee. “3 The Success of Asian American Studies.” Journal of Asian American Studies 25, no. 2 (2022): 187–94. https://doi.org/10.1353/jaas.2022.0016.