Breaking the Silence: How The Stigmatization of Women’s Mental Health Influenced the Written Word

The treatment of female madness during the 19th and 20th centuries heavily influenced what was written during the time. This exhibit dives into the impact of the written word, specifically through literature and gravestone inscriptions, in order to reflect on how past narratives of mental health and misogyny affect the public perspective. By unraveling this stigmatization and creating a new narrative for women’s mental health through the use of artifacts from the Wesleyan Special Collections Library, this exhibit aims to comprehensively explore the intersection between gender, mental health, and social perceptions.

Historical Context

The term “hysteria” was first coined in ancient Greece by Hippocrates, who got the idea of female madness from his Egyptian and Greek predecessors, who chalked it up to the movement of the uterus (Tasca). The earliest mention of the spontaneous movement of the uterus causing delusion was identified in an Egyptian papyrus dating back to 1900 BCE. Later, in ancient Greece, the Argonaut Melampus, who was considered one of the founders of psychiatry, stated that women who went mad acted that way because they weren’t having sex and that they could be healed when they “recovered their wits” and had intercourse with a man. Plato and Aristotle both agreed, arguing that the uterus is unhappy when a woman isn’t pregnant. Hippocrates derived hysteria from the Greek word “hysteron,” which means uterus. These misogynistic notions continued to trickle down through the Roman Empire, the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance (Tasca). As science became more advanced, most physicians no longer believed that hysteria was caused by the uterus moving throughout the body and that it was instead a general nervousness of the brain. However, they did still believe that hysteria was a female disease. As a result, women’s mental health was heavily stigmatized in Europe and the Americas by the 19th and 20th centuries, and treatments were often abnormal, unhelpful, and unnecessary.

Diagnosis and Treatment in the 19th and 20th Centuries

One of the most prominent cures for female mental health concerns during the 19th century was the “rest cure.” Invented by S. Weir Mitchell, the “rest cure” instructed patients to follow a strict regimen of bed rest and seclusion for as little as six weeks. During this time, Mitchell explained to his patients that he would be in control of every single aspect of their lives and that any concerns about his practice would need to be disregarded immediately (Bassuck 247). If the women in his care ever became unwilling to follow the strict bed rest regime, Michell would give them sleeping pills to make them more docile. Additionally, he implemented strict censorship of outside news and barred his patients from interacting with friends or family in order to control their nervousness. While Mitchell argued that this treatment was extremely helpful to women suffering from “nervousness,” many women who followed the rest cure became even sicker (Bassuk). Charlotte Perkins Gilman was one of these women, writing in 1913 that her doctor told her, after suffering from nervous breakdowns for several years, that “there was nothing much the matter with me, and sent me home with solemn advice to ‘live as domestic a life as far as possible,’ to ‘have but two hours’ intellectual life a day,’ and ‘never to touch pen, brush, or pencil again’ as long as I lived” (Gilman). Luckily, with the help of a friend, she returned to her normal life as a writer.

Women who were deemed too much of a handful to be treated at home were sent to asylums. On top of those who were considered “nervous,” asylums took in women who suffered from Alzheimer’s, dementia, epilepsy, depression, anxiety, and physical limitations (Showalter 162). In December of 1851, Charles Dickens took a trip to St Luke’s Hospital for the Insane, where he observed that out of the 18,759 inmates that St. Luke’s Hospital had taken it over the years, 11,162 had been women. “The experience of this asylum did not differ, I found, from that of similar establishments, in proving that insanity is more prevalent among women than among men… Female servants are, as is well known, more frequently afflicted with lunacy than any other class of persons,” Dickens wrote (Showalter 157). Of course, that isn’t actually true. It just happened to be that institutionalized misogyny and classism within the medical field made it seem that way. For example, many prominent experts, such as Mitchell, believed that women were inherently too emotional, which caused them to be more prone to “inappropriate displays of feelings” (Bassuk 249). Interestingly, prior to the middle of the Victorian era, men were actually more likely to be institutionalized for insanity (Showalter).

From Books to Gravestones: The Widespread Effect on the Written Word

After Charlotte Perkins Gilman began to disregard her doctor’s advice, she decided to write a short story called The Yellow Wallpaper (1892), which followed the story of a woman who went insane after a doctor prescribed her the rest cure for postpartum depression. “Being naturally moved to rejoicing by this narrow escape, I wrote The Yellow Wallpaper, with its embellishments and additions, to carry out the ideal (I never had hallucinations or objections to my mural decorations) and sent a copy to the physician who so nearly drove me mad,” she wrote (Gilman). She was not the only one whose writing was influenced by insanity. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, several books and short stories that dealt with madness and its treatments were published.

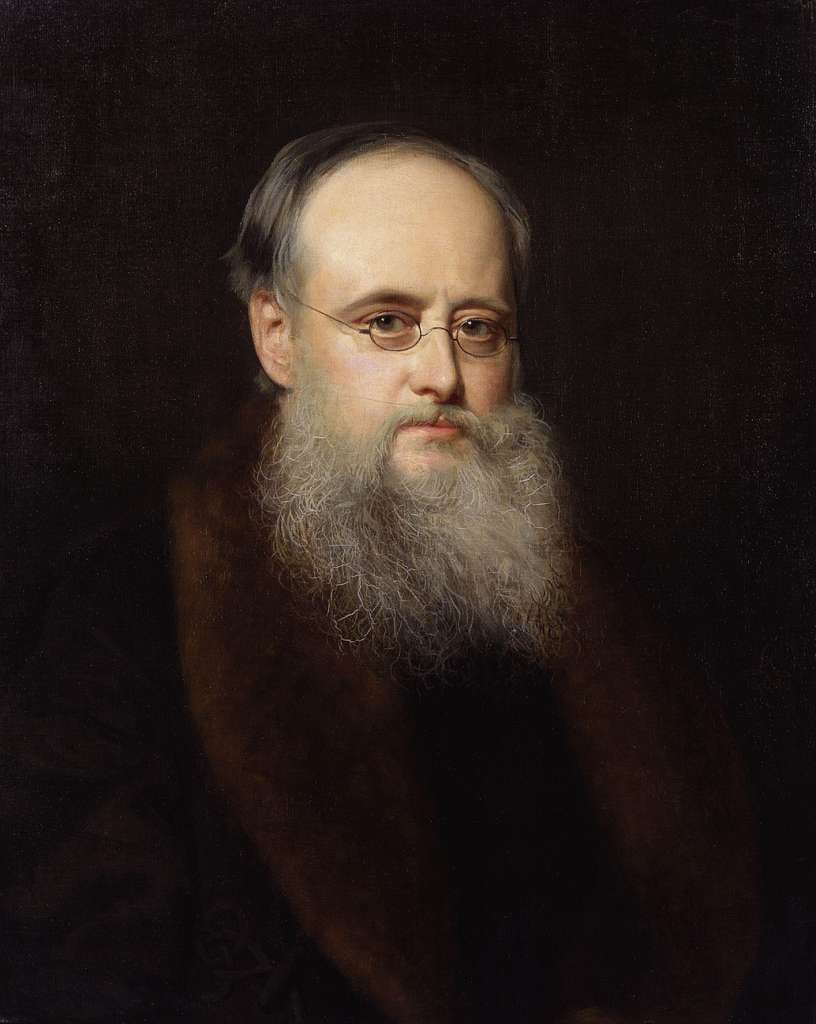

Several years prior, in 1847, Charlotte Brontë published Jane Eyre, which follows the life of a woman who falls for her employer, Mr. Rochester. Unbeknownst to Jane at the time, Mr. Rochester was already married to a woman named Bertha Mason, whose mental health began to decline after the two got married (Donaldson). In place of treatment, Rochester locked Bertha in the attic, where she later escaped and wreaked havoc on the estate. Several scholars, including Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, have researched the character of Bertha Mason and why Brontë may have included her in Jane Eyre. They concluded that madwomen present in literature written by women in the 19th and 20th centuries projected the fear of a male-dominated literary society. According to Gilbert and Gubar, female authors such as Brontë included these characters as a way to rebel against patriarchal authority (Donaldson 99). It is important to note, however, that male authors also successfully wrote about madwomen. For example, English writer Wilkie Collins published an extremely successful novel entitled The Woman in White, which tells the story of Walter Hartight, who encounters a woman named Anne who was previously committed to an asylum for her erratic and nervous behavior. The fact that male authors were also writing about female insanity reflects border societal anxieties and cultural attitudes towards mental health.

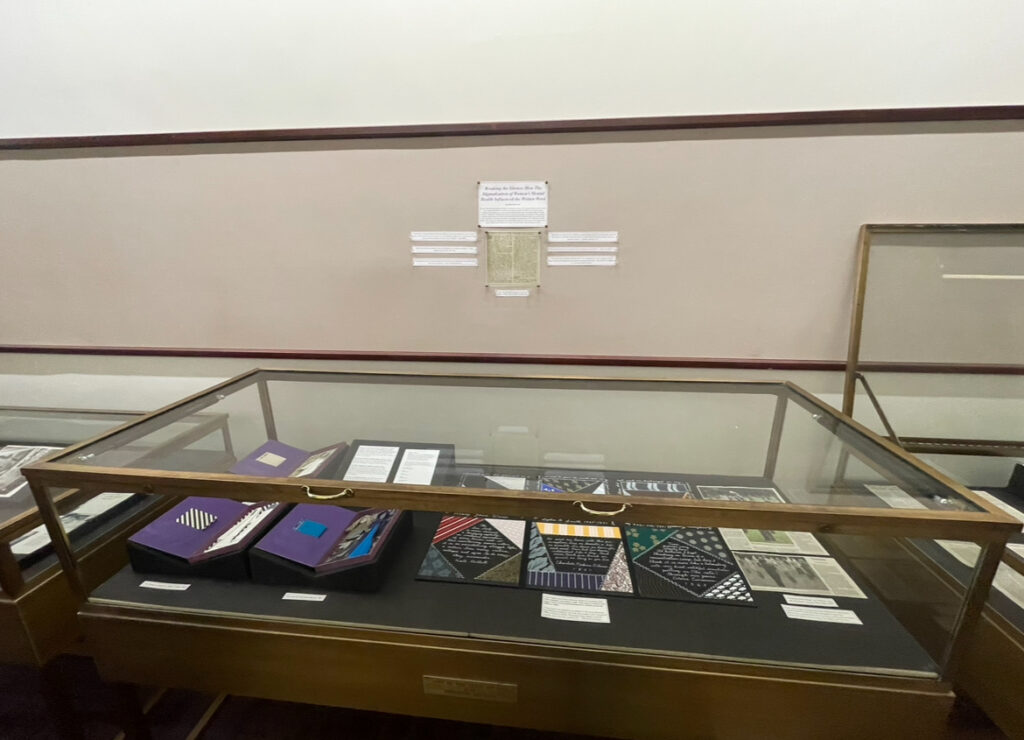

Literature was not the only form of written record affected by the stigmatization of women’s mental health. At the Conneticut Valley Hospital, a state owned and operated psychiatric facility that opened in 1868, patients who passed away were buried in graves marked only by numbers, illustrating the dehumanization of individuals who suffered from mental illness. According to an article by Josh Kovner that was published in the Hartford Courant (see “Naming the Dead” in the display case), a Wesleyan student found a list of names corresponding to CVH graves in the late 1990s. Subsequently, in May of 1999, a group of Middletown, CT clergy members gathered at the cemetery and read the names of graves 1 through 100. They continued to do this each may until every single name was read aloud. Additionally, a patient-run cafe at CVH sponsored the construction of three granite memorials with the names of those buried at the cemeteary.

The Purpose of this Exhibit

My main goal of this exhibit was to give some of the power back to the women who fell victim to misogynistic mental health practices by examining societal preceptions of madness and misogyny. I decided to focus my exhibit on the written word as writing serves as a primary source of insite into these cultural attitudes and practices. Additionally, the Welseyan Special Collections Library has an extensive collection of artists books, newspaper clippings, and literature that deal with the stigmatization of women’s mental health during the 19th and 20th centuries. Ultimately, examining these sources allowed me to engage critically with the past, challenge long held stereotypes, and promote a deeper understanding of mental health and gender. Hopefully, my exhibit does the same for my viwers.

Works Cited

Bassuk, Ellen L. “The Rest Cure: Repetition or Resolution of Victorian Women’s Conflicts?” JSTOR, Poetics Today, 1985, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1772132. Accessed 26 February 2024.

“Charlotte Perkins Stetson Gilman | National Portrait Gallery.” National Portrait Gallery, https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.83.162. Accessed 17 May 2024.

Donaldson, Elizabeth. “The Corpus of the Madwoman: Toward a Feminist Disability Studies Theory of Embodiment and Mental Illness.” NWSA Journal, vol. 14, no. 3, 2002, pp. 99–119. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4316926. Accessed 23 Apr. 2024.

Peale, Charles Willson, and george richmond. “Charlotte Brontë Richmond – Public domain portrait painting.” PICRYL, https://picryl.com/media/charlotte-bronte-richmond-a2eccf. Accessed 17 May 2024.

Perkins Gilman, Charlotte. “Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “Why I Wrote The Yellow Wallpaper” (1913).” The American Yawp, 1913, https://www.americanyawp.com/reader/18-industrial-america/charlotte-perkins-gilman-why-i-wrote-the-yellow-wallpaper-1913/. Accessed 26 February 2024.

Showalter, Elaine. “Victorian Women and Insanity.” JSTOR, Victorian Studies, 1980, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3827084?searchText=female+hysteria&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dfemale%2Bhysteria&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&refreqid=fastly-default%3Acc5f8b9266311a892c0d99a9a3b2a563. Accessed 26 February 2024.

Tasca, Cecilia, et al. “Women And Hysteria In The History Of Mental Health.” National Library of Medicine, 19 October 2012, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3480686/. Accessed 26 February 2024.

Wikipedia, https://picryl.com/media/william-wilkie-collins-by-rudolph-lehmann-94f5bf. Accessed 17 May 2024.

Wikipedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=72741569. Accessed 17 May 2024.