Wesleyan, Interrupted: History, Inclusion, and Progress

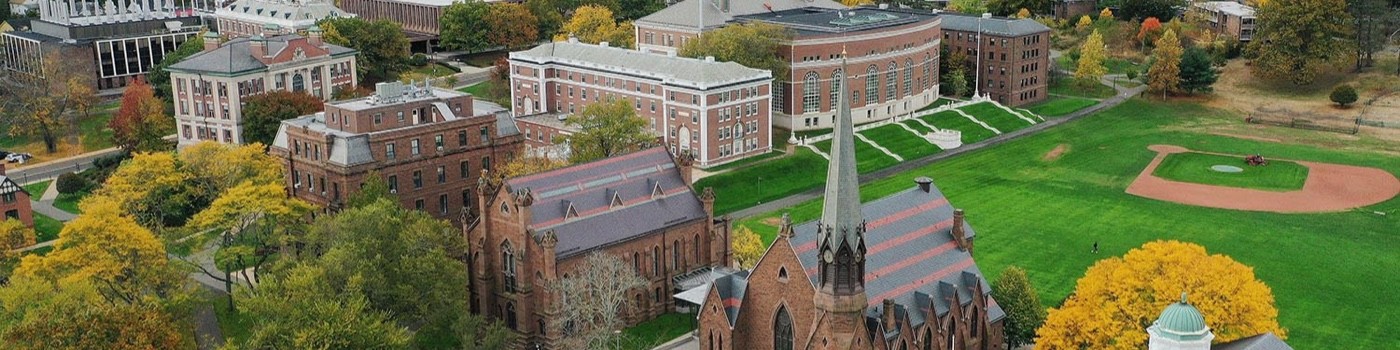

Wesleyan today is nearly unrecognizable after almost 200 years of growth. Throughout its history, Wesleyan has struggled with inclusion. This exhibit considers how ideas of inclusion have changed over time. When the university has embraced inclusivity and welcomed those who seek education regardless of race, gender, or status, it has found success. This exhibit aims to express that progress for a better society can start through the power of inclusion.

My Exhibit Title

For the name of my exhibit, I took inspiration from both Dutch Golden Age art and 90s drama movies. Girl Interrupted at Her Music is a painting made in 1658 by Johannes Vermeer, author Susanna Kaysen would later write a memoir and subsequent movie titled Girl, Interrupted. These pieces are all about normal evolution or development being interrupted by life events. Harry Abrams describes the metaphors behind the painting. He says, “Music-making, a recurring subject in Vermeer’s interior scenes, was associated in the seventeenth century with courtship. In this painting of a duet or music lesson momentarily interrupted, the amorous theme is reinforced by the picture of Cupid with raised left arm dimly visible in the background.” (Abrams, 1996). The music lesson depicted is interrupted just as the young girl’s adolescence is interrupted by courtship. This symbolizes the struggles of female adolescence interrupting healthy development and personal evolution. This random art history lesson matters because this theme can be seen in Wesleyan’s history and this is why I choose to name my exhibit as such. Just as courtship interrupted the girl’s evolution, Wesleyan’s struggle with the historical status quo interrupted its want and drive for inclusion and societal evolution.

Girl Interrupted at her Music.

When Inclusivity Goes Wrong

Wesleyan University today is attributed as incredibly liberal and progressive. Wesleyan is known for its safe haven persona, accepting and representing all races, religions, sexual orientations, and identities imaginable. A Wesleyan Argus article further describes this. “The University has drawn attention for a wide range of anomalies: highly unique fashion, nude dorms, selective admissions, an open curriculum, and the stereotype that students are all liberal, artsy hipsters” (Ramseur & Harkless, 2020). This progressive atmosphere attracts like-minded students and faculty further creating the idea of Wesleyan as a progressive utopia. This is portrayed in the 1994 comedy “PCU” written by two Wesleyan graduates Adam Leff and Zack Penn. “The film is based on the experiences of Leff and Penn at Eclectic Society at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut” (IMDB, 1994). The movie is a satirical depiction of Wesleyan as the “politically correct university.” The plot pits Greek life students against the protests of special interest groups like radical feminists, Afrocentric groups, and multiculturalism as a whole. This idea that Wesleyan is some form of a progressive utopia makes it easy to think that it has always been this way. This assumption is wildly incorrect. While Wesleyan has frequently been ahead of its time regarding social ideals of inclusion, many pioneers who fought against the status quo of their time at Wesleyan have been left behind in battles for progress. This exhibit seeks to honor some of these pioneers that helped build Wesleyan into the institution it is today.

Wesleyan has repeatedly attempted to promote inclusivity before others are ready, and time and time again it has been beaten down by the status quo. This can be illustrated best by the university’s history with racial integration and co-education. Although Wesleyan was one of the first colleges to accept black students, its struggle against racism continued. The first black student Charles B. Ray left after only two months, largely due to protests against his enrollment. A university report describes Mr. Ray’s experience during his short time at Wesleyan. It says, “Once he came to take meals with the other students on campus, many of the Southern students, as well as some from the North, objected to his presence. A number threatened to withdraw from Wesleyan unless Ray was thrown out. At that point, Ray declared that he no longer wished to remain at Wesleyan, but Fisk asked him to stay, and called on the Board of Trustees to make a final decision. The Board voted against Mr. Ray’s continuing [as] a member of this institution” (An Intervention in 185 Years of Wesleyan History: Final Report of the Presidential Equity Task Force, pp. 1). Few black students attended Wesleyan until the 1960s when black students’ admission began to rise.

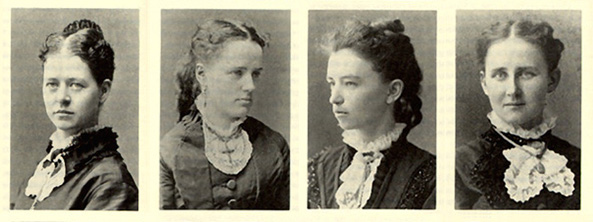

Co-education shares a similar history at Wesleyan as racial integration. While Wesleyan was one of the first colleges to accept women in 1872, co-education eventually ended in 1912 due to pushback from students, administrators, and alumni. Co-education returned in the late 1960s and its supporters continued to fight discrimination and social tension on campus. Wesleyan’s past with racial integration and co-education illustrates that it has not always been the so-called progressive utopia it is today. It is true that Wesleyan attempted greater inclusion far earlier than other similar institutions. However, as detailed above, these attempts struggled against and commonly were subdued by social and racial prejudice.

A roster of African-American students at Wesleyan from 1831-1964. The notes on the right of the names describe how many of these students would end up leaving Wesleyan, further demonstrating the struggle of early inclusion efforts.

Wesleyans first black graduate Wilbur Fisk Burns.

Wesleyans first four women.

When Inclusivity Goes Right

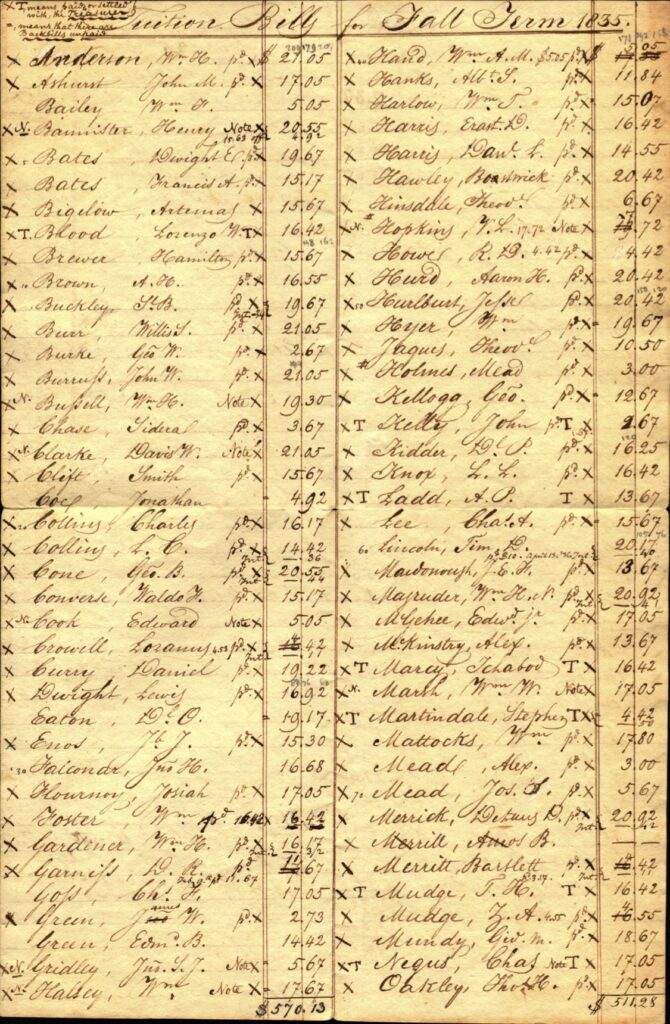

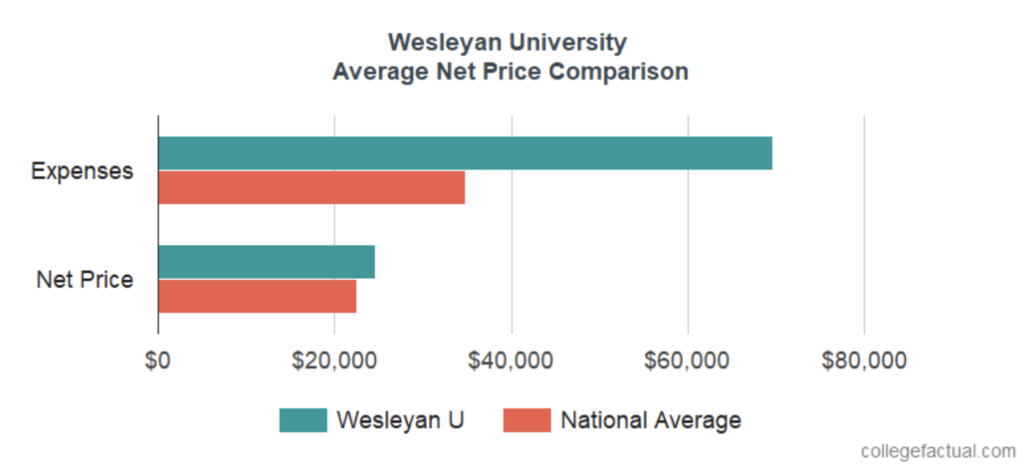

While Wesleyan has historically struggled with inclusion it also has its own success stories. One of these stories is the tuition and accessibility of Wesleyan. While the sticker price of full Wesleyan tuition today is quite polarizing, it can also be deceptive. Full tuition at Wesleyan University is very expensive, but what is not shown is that 40% of students are on some sort of need-based financial aid. Wesleyan guarantees 100% of need-based financial aid, it is one of the few colleges to do so. In 1835 tuition was around $30-$40, a price far cheaper than similar alternatives such as the $75 average tuition of Harvard in the 1840s. To this day there is a continual fight on campus for economic and financial inclusion. This varies from personal finance workshops to organized petitions for state-funded aid. The objects featured below are examples of this. One example featured is a 1977 Wesleyan Argus article detailing how students and University president Bennet organized a 1200-signature petition to convince then Connecticut Governor Grasso to increase aid for students attending private colleges. They would go on to successfully bring $4 million in aid for Connecticut students attending private colleges and universities.

Currently on campus today the examples are evident everywhere. Wes Swings student workers are in the middle of a fight to unionize, students continually pressure President Roth to invest ethically, Bird scooters were taken off campus for visually impaired students, and there are signs in dorm bathrooms telling students that if they conserve water the university can use more money for financial aid. One of the most salient examples of Wesleyans drive for inclusion is President Roth mandating residential fraternities to become fully co-educational. “Roth stated that he believes that the coeducation policy is in line with the University’s previous actions and values. This step is in keeping with our commitment to enhancing an equitable and inclusive residential learning experience at Wesleyan. We have long experience with co-educated Greek societies, and I look forward to working together to ensure a successful transition” (Laermer, 2014). Fraternities and sororities are still allowed to remain on campus as social organizations however they now must also accept both genders if they wish to operate residential spaces. This choice is motivated by the assertion that single-gender housing is inequitable, a stance with the faint undertone of the objection to ‘separate but equal’. Multiple groups have already accepted this change and have found great success. Psi Upsilon and the Eclectic Society are two such groups. Inclusion is something that Wesleyan students and faculty alike are both invested in.

A tuition bill from 1835. In 1835 annual tuition was around $30-$40, a price far cheaper than similar alternatives such as the $75 average tuition of Harvard in the 1840s.

Another example of inclusion in the Wesleyan student body; three women of the class of 1892 pose for a portrait. Attending college at a time even before gaining the right to vote. For context, the first woman to graduate from Harvard University was in 1917. Co-education at Wesleyan faced a similar reality to racial integration. While Wesleyan was one of the first colleges to accept women in 1872, co-education eventually ended in 1912 due to pushback from students, administrators, and alumni. Co-education eventually returned in the late 1960s.

Wesleyan Students have often led the charge for inclusion. In 1977 Wesleyan students and University president Bennet pioneered a 1200-signature petition to convince Connecticut Governor Grasso to increase aid for students attending private colleges. This demonstrates how Wesleyan students and faculty have strived to create an inclusive environment.

The abandoned house of the Gamma Phi chapter of the Delta Kappa Epsilon (DKE) fraternity. 276 High Street remains off-limits to students since the fraternity was suspended due to violating the Universities COVID-19 agreement in 2021.

Signs posted in Wesleyan’s Exely Science Center arguing to have Wesleyans food service contractors organize into a union. The sign reads “Wesleyan can afford a 100% union food service on campus. All workers deserve to be paid fair wages for their labor. Wesleyan can afford to ensure its food service contractors respect union organizing and pay fair union wages.”

Modern price comparison between Wesleyan tuition and the national average.

This is a podcast Wesleyan has created on Soundcloud. Episodes vary in topics and presenters. This episode is about former student experiences with the financial aid office and how supported students felt. The presenters are all former Wesleyan students.

Growth and Progress

Why has Wesleyan made it to today? Why has Welseyan become such a respected and widely known university? Is it because of our athletics? Is it because of Usdan food? Is it because of President Roth’s dog? Maybe, but probably not. These questions are almost impossible to measure but I believe that success is largely a product of the values behind the organization. So let’s look at what Wesleyan has valued since its founding in 1831 all the way to 2023. While it has struggled across its history to achieve its goals of inclusion, Wesleyan has tried to promote inclusion throughout its journey. Wesleyan’s first president, Willbur Fisk, set out an enduring theme at his inaugural address in September 1831. President Fisk said, “Education serves two purposes: the good of the individual educated and the good of the world.” There is no way to prove exactly why Wesleyan has stood the test of time, but the goal of inclusion and education for all seems to be at the core of Wesleyans identity.

A map of Wesleyan University and the surrounding land from the 1850s. Wesleyans campus is not more than a handful of buildings and is overshadowed by the far larger Indian Hill Cemetery and Burial Ground. This shows how small Wesleyan once was and shows how prominent Wesleyan has become in the Middletown landscape today.

Wesleyan University campus in the summer of 2011. Both buildings you see are not on the map above, this demonstrates the growth of Wesleyan as an institution.

The photos below exhibit just a few of the dozens of Wesleyan student identity organizations that are active on campus, these groups demonstrate the inclusive environment Wesleyan facilitates on its campus today.

“Education serves two purposes: the good of the individual educated and the good of the world”

– Wesleyan’s first president Wilbur Fisk in his inaugural address. September, 1831.

Sources and Citations

Special Collections Objects:

- Wesleyan tuition bill from 1835. (Student records: financial and general, box: 8)

- 1977 Wesleyan Argus article. (Box: 1, Folder: 4, Item: 6)

- Group photo of three women from he class of 1892. (Box: 2, Folder: 5, Item: 5)

- Campus map from 1850. (Wesleyan Campus Maps, Box: 1, Folder: 1).

- Roster of African-American Students from 1831-1964. (Hewlett Diversity Archive, Box: 2, Folder: 5)

- Portrait of Wilbur Fisk Burns from the 1860 class album of William Wardell. (Vertical Subject Files, Cabinet 8, Drawer A).

Media:

- Vermeer, Johannes. “Girl Interrupted at Her Music.” Flicker.Com, Rawpixel Ltd, 2 Mar. 2022, https://www.flickr.com/photos/vintage_illustration/51913750940. Accessed 13 May 2023.

- Wesleyan University. “Wesleyan’s First Four Women.” Wesleyan’s First Four Women, Wesleyan Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, https://www.wesleyan.edu/fgss/firstwomen.html. Accessed 13 May 2023.

- Wesleyan University. “Usdan Campus Center Patio.” Photos, For the Media, Wesleyan University Communications, https://www.wesleyan.edu/communications/media/photos/Wesleyan-Usdan-Campus-Center-Patio.jpg. Accessed 13 May 2023.

- College Factual. “Wesleyan University Net Price Comparison.” Wesleyan University Costs & Amp, Media Factual, https://www.collegefactual.com/colleges/wesleyan-university/paying-for-college/net-price/chart-avg-net-price-compare.html. Accessed 13 May 2023.

- Mabel, Joe. “Wesleyan University – DKE.” Wikimedia Commons. 28 March 2012. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wesleyan_University_-_DKE_01.jpg. Accessed 13 May 2023.

- Rabow, Emerson. “Photograph of union flyers in Exely.” 15 May 2023.

- Solnit , Ben, et al. “Stream Storytelling: Ben Solnit ’79 Laura Walker ’79 and Pamela Dorman ’79.” SoundCloud, 9 June 2009, soundcloud.com/wesleyanuniversity/storytelling-solnit-walker-dorman-79.

- “WJC Logo.” Wesleyan Jewish Community , Weebly, https://wesleyanjewishcommunity.weebly.com. Accessed 13 May 2023.

- “Wesleyan Muslim Students Association Logo.” Wesleyan MSA, Instagram , 4 Oct. 2021, https://www.instagram.com/p/CUoQfJOA-3A/?hl=en. Accessed 13 May 2023.

- “@Ujamaa_wesu Logo.” Ujamaa (Wesleyan University’s Black Student Union), Twitter, 5 Mar. 2021, https://twitter.com/ujamaa_wesu. Accessed 13 May 2023.

- Wesleyan Resource Center. “Latinx Spaces at Wes Poster.” Latinx Spaces at Wes, Facebook, 4 Oct. 2020, https://m.facebook.com/events/706442273284439/. Accessed 13 May 2023.

Sources:

- Abrams, Harry. “Girl Interrupted at Her Music.” – Works – Collections.Frick.Org, 1996, collections.frick.org/objects/273/girl-interrupted-at-her-music?ctx=4474c842-00b0-448f-9e7c-7d947c5bf920&idx=11. Accessed 13 May 2023.

- Wesleyan University. “An Intervention in 185 Years of Wesleyan History: Final Report of the Presidential Equity Task Force.” Wesleyan Inclusion Resource Files, 30 Apr. 2016, www.wesleyan.edu/inclusion/resource_files/ETF_Final_Report_May2016.pdf.

- Laermar, Courtney. “President Roth, Board of Trustees Announce Coeducation of Residential Fraternities.” The Wesleyan Argus, 11 Sept. 2014, wesleyanargus.com/2014/09/22/residential-fraternities-given-three-years-to-coeducate/.

- Ramseur, Olivia, and Jo Harkless. “Is Wes Progressive? A Look at the University’s ‘activist’ History.” The Wesleyan Argus, 5 Nov. 2020, wesleyanargus.com/2020/11/05/is-wes-progressive-a-look-at-the-universitys-progressive-history/.

- “PCU (1994).” IMDb, 29 Apr. 1994, www.imdb.com/title/tt0110759/.