Black Wes is the exploration of the history and development of blackness at Wesleyan University. This blackness is in relation to the Black Wesleyan community connected by shared struggles and related cultures. Though this community wasn’t created by choice, but forced together by their inherent blackness, they came together to form a strong and interconnected community.

Most institutions have some kind of Black history. This is more true the older the university is, and it is true in the case of Wesleyan University, founded in 1831. This history can be demonstrated through the university’s construction, the student population, or even local movements around the institution.

When walking around areas of Wesleyan, such as Fisk Hall, you’ll find plaques on the walls describing hall takeovers and Black presence, Black firsts, and Black determination to make Wesleyan a more inclusive place. Not forgetting that this university has a dorm named after Malcom X, commonly called X House. And while these things seem normal to have now, expected even of the university to provide, it took lots of work to get to the point where Wesleyan’s Black community is today. It took struggle, bravery, and firmness. Those who came before us had to stand against a white, established institution for what they believed in and what they felt they had the right to have. And it is likely that if they had not, the Wesleyan we all know today would be different.

Wesleyan’s First Black Student

Wesleyan was founded in 1831. While this exploration of Wesleyan’s Black history started in the mid 1900s, around 1950-1960. It was assumed that this would have been Wesleyan’s start with black enrollment as this was a turning point in the nation when it came to black enrollment. But, it was actually in 1832, a year after Wesleyan’s founding, that the university accepted and enrolled its first Black student. This student was Charles B Ray who later became a major abolitionist in the north. While it would be great to say that Ray’s experience at Wesleyan was setting a clear curb for the rest of the nation, that wasn’t the reality of Ray’s enrollment in the university. His peers protested his enrollment so much so that Ray left the university 7 weeks after he first set foot on Wesleyan’s campus. And then when Wesleyan went on to cater to primary white, male students for the next 120+ years, it can make the Black history at Wesleyan seem bleak. Despite the large time gap between 1832 and the early 1960s, I chose to implement Ray not only because he was the first black student at Wesleyan, but because I felt this still spoke to the mindset of the establishment at the time. It’s important to remember that slavery had not been abolished in Connecticut at the time of Ray’s enrollment and it was during the 1830s that slavery had become a hot topic of sorts within the New England area. This is to say that accepting and enrolling Ray into the university was a statement and stance on slavery and black capability. And it is the openness of the institution to listen to protests and student voices that have aided in the growth of the black community over the years. Ray’s enrollment goes to show more of what kind of institution Wesleyan has the capability to be.

Wesleyan Bans Black Students

After Charles B. Ray left Wesleyan, the university decided to ban the enrollment of black students from the university. Although this banishment only lasted for three years, black students still weren’t a priority, focus, or general interest in the enrollment committee of the university until the 1950s-1960s.

Martin Luther King Jr. Visits Wesleyan University

It was in the 1960s that Wesleyan University began to show an active interest in black student recruitment. The time of this new interest falling in line with the peak of the Civil Rights Movement may appear to come across as coincidental, but it could also be that during this time the students and the institution began to get involved in local protests involving civil rights issues. A group of events that stand out are Martin Luther King’s visits to Wesleyan University. In the early 1960s, Dr. King visited Wesleyan four times. In 1964, he gave the baccalaureate commencement speech and received an honorary doctorate.

This following audio is the 1964 Commencement speech that Martin Luther King gave.

Timestamps:

- Introduction 0:00 – 2:06

- Singing 2:06 – 4:39

- Introducing Martin Luther King 4:39 – 10:42

- Martin Luther King’s Speech 10:42 – End

The interest Wesleyan’s student body held in Dr. King was both fascinating and radically different from that of Wesleyan students in the 1830s. It is understandable that there would be a difference due to the time period, 1832 versus 1960. But, given that Wesleyan catered to white males first and foremost, this development highlights the moral and ethical background of the school.

Furthermore, Dr. King’s continuous visits to the university, on top of other events during the time, serve as a precursor to future black student protests on campus. This isn’t to say that the protests were because of Dr. King’s visits, but it is to suggest that his visits impacted the attitudes of the white populations at Wesleyan, allowing them to be more open to hearing the voices and perspectives of their Black peers. This is significant because during this period, although Wesleyan had a handful of black students admitted to the university and white students participated in local protests, the school existed in two distinct and opposing factions, “White and Black Wesleyan.”

Black Students Make Their Voice Heard

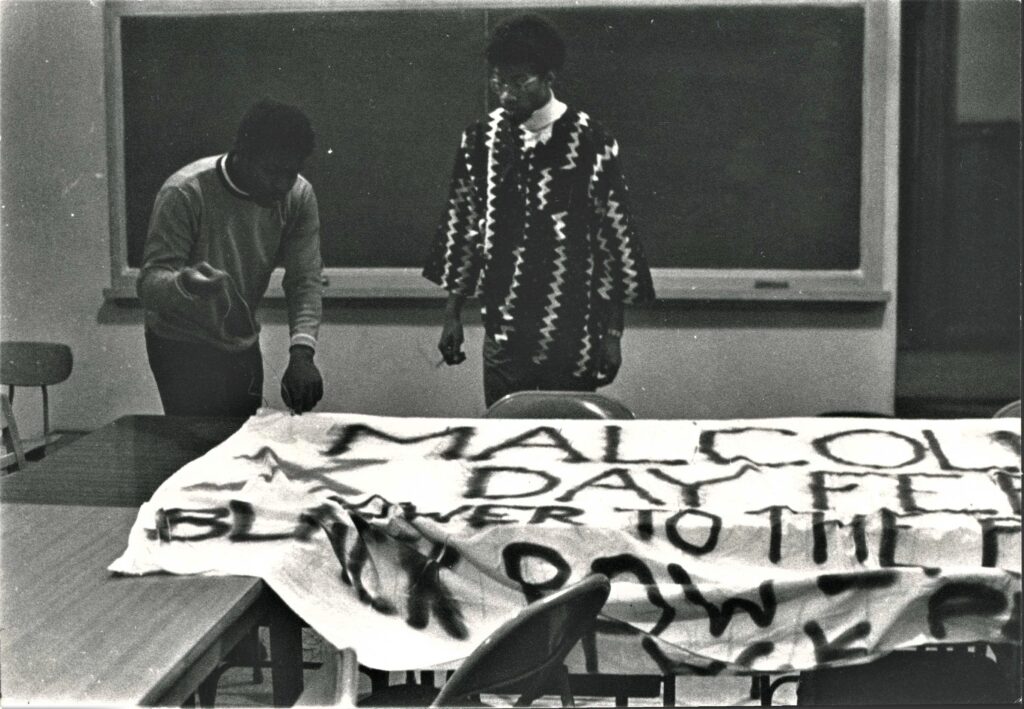

It was in 1969 that the Black community at Wesleyan decided that they wanted a day to commemorate Malcom X in a similar way in which the university had memorialized Dr. King after his assassination. At first, the students had submitted the request to the institution for a day off from classes to memorialize Malcom X. When the administration rejected the request, Wesleyan’s Black community decided to organize the Fisk Hall Takeover. They would force a day off from class by taking over the Fisk building, the major academic hall during that time.

But the protest wasn’t just about granting a day off. It was also about the Black community feeling as if their voices weren’t heard and they didn’t have any priority. Because while the university had dedicated time to enrolling Black students, the quality of life for black students at Wesleyan was far below the quality of life for white students.

The impacts of the Fisk Hall Takeover are still seen today. One key example was the conversion of the Wesley House, named after the founder of Wesleyan, to the Malcolm X House, in honor of the late Malcolm X. This housing became a dorm catering to the Black population at Wesleyan.

Despite the reasons for protesting, it was also the ability for them to protest safely and efficiently on Wesleyan campus that should be highlighted as well. In an era of high racial tensions, Black students at Wesleyan were able to protest and voice their complaints without repercussions of their institution, such as removal from the university. This isn’t to diminish their entire purpose. Protesting, but to show how the willingness of the institution had grown since 1832.

The following video is a reenactment of the Fisk Hall Takeover by Wesleyan’s Black community in 2014.

Black Students Weren’t Alone

So far, most of the emphasis of Black Wes has been on students and guests who have visited the university. But this isn’t to say that they were the only groups involved in advocating for inclusivity, diversity, and a safe campus for those of color. Faculty contained many leaders who helped in aiding their students in times of hardship and other race related issues. Black Wes is a community and that community spreads beyond just students.

Edgar Beckham started as a student at Wesleyan, class of 58. In 1961 he became the first Black professor at Wesleyan and in 1973 he became the first Black Dean at Wesleyan. But these accomplishments aren’t all that make him stand apart. Beckham was a vocal advocate for diversity and inclusivity at Wesleyan’s campus. He was involved with Ujamaa, a Black student union and aided in setting up and facilitating the Fisk Hall Takeover. He was the very one who gave the students the keys to get into the building before classes started. He helped to facilitate Wesleyan’s NAACP program and led discussion on the importance of diversity in education. A student of his quoted him saying…

“What I want to urge you to do is live your lives on campus in ways that turn diversity into an educational asset, one that feeds your curiosity and trains you in observation, analysis, and critical thinking. And diversity can do that, if you recognize it as an educational tool, a rich store of information like a library, an apparatus, like the ones in the laboratory, that can support your inquiry into new domains of knowledge.”

Edgar Beckham, quoted by Alford A. Young Jr. Class of 88

Beckham emphasized the importance of voices and protest as well as peacefulness. He relayed understanding of the frustrations that come along with fighting for your place in society, but he guided his students to conduct themselves in ways that wouldn’t just get them seen but heard and listened to. His guidance was essential to helping young Black leaders navigate Wesleyan’s campus and racial incidents.

Another faculty member that played a role in working towards diversity and inclusivity at Wesleyan was Jerome Long. He was the second Black tenure-track professor in 1971, and the first tenured Black professor in 1974. Long was very vocal about the need for a Center for African American Studies. During that time, the university had history courses discussing topics relating to African American history, but most, to nearly all, were taught by white professors. Long, as the chair of a committee, worked on establishing the Center for African American Studies on Wesleyan’s campus and creating a dedicated space to learn about African Americans’ history. In addition, Long served as a chair of the African Studies Committee. Long dedicated time to supporting those who didn’t have much support, especially in comparison to their white peers. The Mellon Minority Undergraduate Fellowship, now Mellon Mays, held Long as their first coordinator. This fellowship works to support underrepresented students in research be it during the school year or in the summer.

Black and White Wes Come Together

Despite White and Black Wesleyan existing as two different entities for so long, in the 1990s, there was a shift. Perhaps it is a result of further discussion on Black rights and perspectives. And with the escalation of hate crimes on campus, the two communities had to come together at some point or another. But them joining into one Wesleyan community wasn’t disastrous, no, the two groups found similarities among one another. They began to speak out about Black students’ treatment on campus together in groups of white and Black students.

A result of this was the creation of Unity Day, which was a day when people came together. As racial tensions at the university began to rise, students came together as a protest to the fire bombings and vandalism that occurred at the Center for African American Studies. Firebombs were hurled at the president’s office, the Malcom X basement, and other places, and they were vandalized with derogatory language and insults.

As well as protesting for their rights on campus, students at Wesleyan University were also very active within the local community in Middletown. Students from Wesleyan University met on Main Street in 1995 to protest police discrimination against black individuals on the basis of their race. They marched through the streets as a single unified group, the color of their skin didn’t matter. This journey toward unification is more representative of how Wesleyan is presented today.

Final Thoughts

All of this is to not just show the Black development at this institution, but to say that what we have today on campus is something that was worked for. From dorms to student groups to academic centers, those within the Black Wes community were leaders in establishing these as normalities on Wesleyan’s campus.

And if you explore more about Wesleyan’s history with its black community, there will be moments where you’ll believe you’re reading about a different school, one further south. Especially when you touch on topics like fire bombings on the Malcolm X House, KKK rallies, and other hate that’s been spread around campus targeting the Black community. But no matter how difficult it is to accept the past of this institution and no matter the progress made, it is imperative to acknowledge the past of this university or any university whether that be its historical demographic or social/political views. Ignoring histories like these is not only ignoring the reality of the world that brought you to this point today, but it erases the work done by others to get us where we are today. Histories like these need to be remembered, taught, and furthermore, these histories should bring about a sense of pride in the work done by those before us as a way to commemorate their strength and efforts.

Archival Sources

BLK WES Introduction

- Campus I, 1851-1878 – Photos, Box:29, Folder: 1. Series 7a: Paintings, Objects, Areas, Facilities, Landscaping, Buildings General, 1000-176. Special Collections & Archives, Olin Library, Wesleyan University, Middletown CT.

Martin Luther King Jr. Visits Wesleyan University

- Photo, Commencement 1964, Martin Luther King Denison Terrace, Vertical (Subject) Files, 1964 General Folder, MLK 17-078. Special Collections & Archives, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT, USA.

- Photo, Martin Luther King College of Social Studies talk – wide view, Vertical (Subject) Files, 1964 General Folder, MLK 17-078. Special Collections & Archives, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT, USA.

- TW 59: Baccalaureate service: Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., Denison Terrace, June 7, 1964, Box: 8, Item: 1. Wesleyan University audio visual collection, 1000-078. Special Collections & Archives, Olin Library, Wesleyan University, Middletown CT.

Black Students Make Their Voices Heard

- Fisk Hall Takeover: Designing Protest Banner, February 21, 1969, Box: 4, Folder: 18. Wesleyan University Hewlett Diversity Archive, 1999-061. Special Collections & Archives, Olin Library, Wesleyan University, Middletown CT.

- Fisk Hall Takeover: Gathering in the Doorway February 21, 1969, Box: 4, Folder: 18. Wesleyan University Hewlett Diversity Archive, 1999-061. Special Collections & Archives, Olin Library, Wesleyan University, Middletown CT.

Black Students Weren’t Alone

- Photograph of Beckham, Edgar teaching a Class, Box: 2, Folder: 25. Wesleyan Hewlett Diversity Archive, 1965-1999. Special Collections & Archives, Olin Library, Wesleyan University, Middletown CT.

Black and White Wes Come Together

- Unity Day Protest, 1990, Box: 4, Folder: 12. Wesleyan Hewlett Diversity Archive, 1965-1999. Special Collections & Archives, Olin Library, Wesleyan University, Middletown CT.

- March for Police Accountability, Main Street, 1995, Box: 4, Folder: 9. Wesleyan Hewlett Diversity Archive, 1965-1999. Special Collections & Archives, Olin Library, Wesleyan University, Middletown CT.

- March for Police Accountability, Main Street, 1995, Box: 4, Folder: 9. Wesleyan Hewlett Diversity Archive, 1965-1999. Special Collections & Archives, Olin Library, Wesleyan University, Middletown CT.

Secondary Sources

- Silverberg, S. (2020, February 3). A brief representative history of African American studies at Wesleyan. Wesleyan University Magazine. Retrieved 2023, from https://magazine.blogs.wesleyan.edu/2019/05/20/a-brief-representative-history-of-african-american-studies-at-wesleyan/

- Wojnar, L. (2009, November 6). A “stronghold of Southern despotism”: First African American student left because of discrimination. The Wesleyan Argus. Retrieved 2023, from http://wesleyanargus.com/2009/11/06/a-stronghold-of-southern-despotism-first-african-american-student-left-because-of-discrimination/

- Larsen, J. (2008, June 30). CHARLES B. RAY (1807-1886). Black Past. Retrieved 2023, from https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/ray-charles-b-1807-1886/

- Hadley, J. (2018, January 13). Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s visits to Wesleyan. Special Collections & Archives at Wesleyan University. Retrieved 2023, from http://sca.blogs.wesleyan.edu/2018/01/13/dr-martin-luther-king-jr-s-visits-to-wesleyan/

- Wesleyan University. (n.d.). Cross Street A.M.E. Zion Church: The Civil Rights Movement. Cross Street Church. Retrieved 2023, from https://crossstreetchurch.site.wesleyan.edu/the-civil-rights-movement/

- Lahut, J. (2017, February 20). Remembering the Fisk takeover, 48 years later. The Wesleyan Argus. Retrieved 2023, from http://wesleyanargus.com/2017/02/20/fisk-takeover-48-years-later/.

- Bernard, S., White, A., & Korman, N. (2014). FISK TAKEOVER. YouTube. YouTube. Retrieved 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t1g5DQSOYUg&t=4s.

- Silverberg, S. (2019). A brief representative history of African American studies at Wesleyan. Retrieved 2023, from https://magazine.blogs.wesleyan.edu/2019/05/20/a-brief-representative-history-of-african-american-studies-at-wesleyan/

- Staff, E. (2023, May 17). Jerome Long, associate professor of religion, emeritus, dies at 91. The Wesleyan Connection. Retrieved 2023, from https://newsletter.blogs.wesleyan.edu/2023/05/17/jerome-long-associate-professor-of-religion-emeritus-dies-at-91/

- Johnson, L. (2018, December 12). Edgar Beckham: “turn diversity into an educational asset.” Wesleyan University Magazine. Retrieved 2023, from https://magazine.blogs.wesleyan.edu/2017/04/01/edgar-beckham-turn-diversity-into-an-educational-asset/

- Johnson, K. (1990, May 9). EDUCATION: At Wesleyan, a Day to Reflect on Racial Tension. The New York Times. Retrieved 2023, from https://www.nytimes.com/1990/05/09/nyregion/education-at-wesleyan-a-day-to-reflect-on-racial-tension.html

- Mabel, J. (2012, March 29). English: North and South College, Wesleyan University, Middletown, Connecticut, USA. Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 2023, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wesleyan_University_-_North_and_South_College_02.jpg