Wesleyan’s Changing Relationship with the Ancestors in our Control

When you first saw the title of this article you were probably confused by the words “Ancestor” and “control.” I would also be confused had I not just embarked on a two month long journey to learn more about Wesleyan’s history and ongoing relationship with the Ancestors.

I have now used the word Ancestor twice (three times if you count the title) but I have yet to provide you with a definition or the necessary context to understand what it means.

Who does the word Ancestor refer to? The word Ancestor refers to

Any physical part of the body of a deceased Native American individual

So why use the term “Ancestor” instead of “human remains”? While the term human remains is the correct legal terminology, the word Ancestors aims to restore humanity to the Indigenous person by recognizing their inherent personhood and ongoing connection to their community descendants.

This brings us to our second unique word: “control”. The word control is a legal word defined by the National Park Service and used to describe the relationship between the institution and the Ancestors they hold.

So, what is the exact definition of Control? “Control,” or “Possession,” is defined as

“Having a sufficient interest in an object or item to independently direct, manage, oversee, or restrict the use of the object or item. A museum or Federal agency may have possession or control regardless of the physical location of the object or item. In general, custody through a loan, lease, license, bailment, or other similar arrangement is not a sufficient interest to constitute possession or control, which resides with the loaning, leasing, licensing, bailing, or otherwise transferring museum or Federal agency”- U.S. National Park Service

Before searching for the legal definition of the word control I was unaware of the fact that it could be used interchangeably with the word possession. Both of these words aim to acknowledge the power that institutions, like Wesleyan, have over Ancestors. I want to draw your attention to a word that is intentionally not used: ownership. This is because the word ownership takes away someone’s personhood, forcefully turning them into an object. No person can be owned by another human.

What is NAGPRA?

Prior to my enrollment in an Introductory level Archaeology class, I, like many of you, had never even heard of NAGPRA. That is until we started our Peopling of the Americas unit. In this unit we not only learned about Indigenous culture through case studies but also about how archeologists have interacted with indigeneity over time. Over the course of a week, I received more education on what NAGPRA is, why it needed to be passed, and the connection between archaeology and American colonialism than most people do in a lifetime.

While it might seem obvious that the United States is heavily influenced by settler colonialism, understanding how this relationship has played out and continues to play out with Indigenous people (both living and deceased) is fundamental to understanding the importance of NAGPRA.

So, what is NAGPRA? NAGPRA, or the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, Is a federal law that requires institutions that receive federal funding, like Wesleyan, to repatriate Ancestors, sacred objects, funerary objects, and objects of cultural patrimony through a process of consultation to culturally affiliated Tribes and Native Hawaiian Organizations.

How NAGPRA Came Into Being

NAGPRA was passed in 1990 after almost 100 years of indigenous advocacy. Since the 1880’s Indgnous people have fought for the right to rebury their stolen Ancestors. However, for almost 100 years there was no legal recourse for Tribes or Hawaiian Organizations. This does not mean that Institutions like Museums or universities were not allowed to return objects, but rather there was no legal framework that required institutions to do so.

But why did museums acquire Ancestors in the first place? In the 1800s and early 1900s white supremacy and settler colonialism objectified Indigeneity. This can be seen in the narrative of the ‘’savage native” and the “vanishing Indian”.

These narratives culminated in Indigenous burial sites being viewed as “resources” from which to gather data on and preserve a “vanishing” race instead of a place that should be treated with reverence. An example of this objectification is that once a burial site was discovered and the collector, archaeologist, or anthropologist got permission from the present day land owner to excavate the property, they would quickly dig up and sell Ancestors to museums, treating them as objects instead of people. This objectification is reflected in museums’ display and treatment of Ancestors in addition to their historical unwillingness to return them to their direct lineal descedants or Tribal communities.

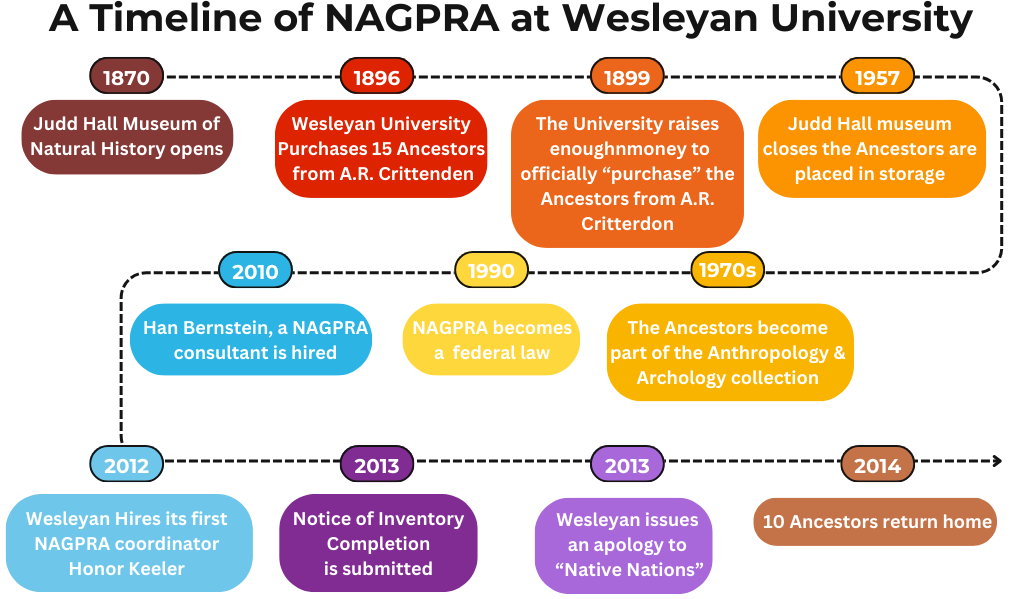

A Timeline of NAGPRA at Wesleyan

To understand the relationship between NAGPRA and Wesleyan’s policies we first need to understand how Wesleyan’s relationship with the Ancestors in its control has changed over time.

In the late 1860s, George D. Barnes, an amateur collector from Dayton, TN received permission from landowners in Hamilton County and Chattanooga County, TN, to access their land and excavate multiple Indigenous burial mounds. Following Barnes’ excavation, he sold some of the Ancestors that he took to A.R. Critterdon, a Middletown resident. Wesleyan University then purchased 15 Ancestors from A.R Crittendon in 1869. However, the institution was unable to pay the full amount ($1,000) until 1899.

At this time, the Ancestors became part of the Wesleyan Natural History Collection located in Judd Hall. It should be noted that there is no evidence that the Ancestors were ever displayed in the museum. In 1957 the Wesleyan Museum closed, resulting in the ancestors being placed in underground storage with the rest of the museum collections until the 1970s when the Anthropology & Archaeology Collection was formed.

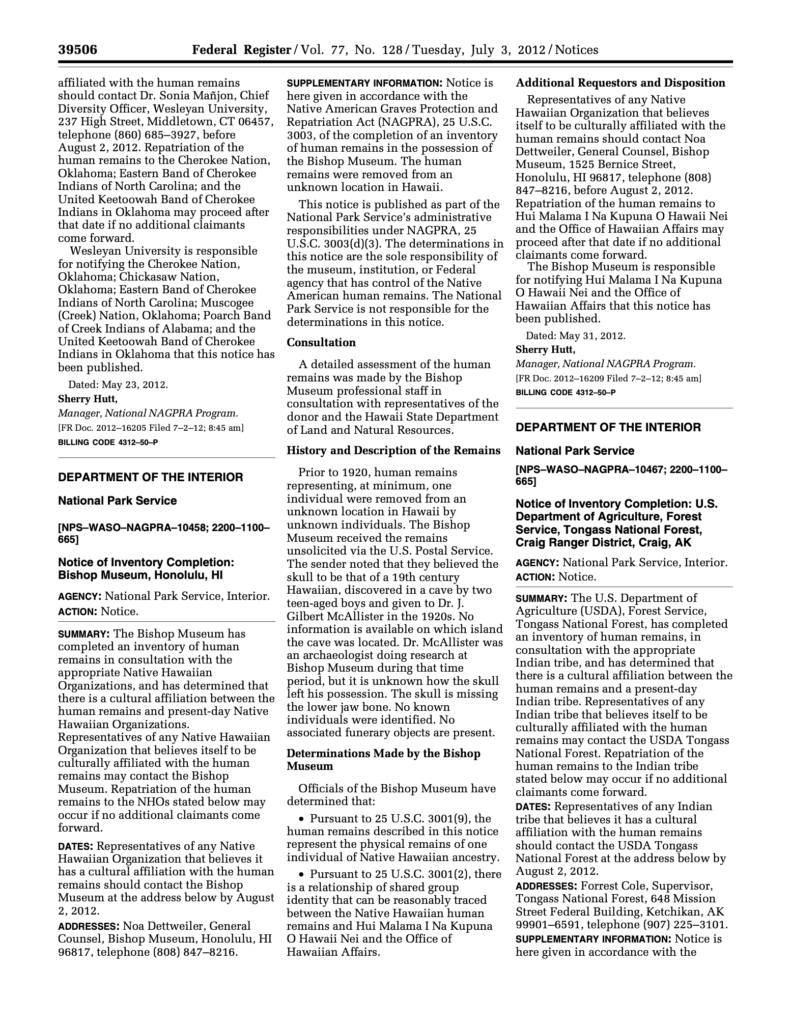

In 1990, after many years of advocacy, protest, and lobbying by Indigenous people and their allies NAGPRA became law. All institutions that receive federal funding, like Wesleyan, were required to submit an inventory by 1995 to be considered NAGPRA compliant.

Because of Wesleyan University’s lack of dedicated resources and staff to this work, it was unable to comply with sections 5 and 6 of NAGPRA, rendering the university noncompliant. In the mid-2000s, members of the administration, including Diversity Officer Sonia Mañjon Provost Rob Rosenthal,and American Studies Professor Kehaulani Kauanui recognized the need to become NAGPRA compliant and treat the Ancestors with a greater level of respect. Around this time, the student group Students for NAGPRA Compliance formed with the goal of raising awareness about NAGPRA and the Ancestors. Starting in the mid-2000s the university began to prioritize repatriation, this marks a fundamental shift in the institution’s understanding and treatment of the Ancestors.

In 2010, Wesleyan University hired Jan Bernstein, a NAGPRA consultant who examined Wesleyan’s history of noncompliance and formulated a plan to get the University into compliance. Two years later, in 2012, Wesleyan hired Honor Keeler, a member of the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma and the school’s first NAGPRA coordinator for a one-year term position. Honor Keeler implemented the compliance plan laid out by Bernstein. This same year, Wesleyan filed its first Notice of Inventory Completion. Additionally, it became clear that it was time to build a respectful space for the Ancestors while they were still in Wesleyan’s control. This respectful space took the form of a blessed cedar lined room with cedar storage furniture that was arranged in consultation with tribal members.

Wesleyan Univresity’s Notice of Invitory Compleation was published on May 23, 2013.

This document details Wesleyan University’s determination of cultural affiliation for 10 Ancestors with the Cherokee Nation, Oklahoma, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians of North Carolina, and the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma. This determination was made through the process of tribal consultation which culminates in the controlling institution determining with which federally recognized Tribe or Native Hawaiian Organization the Ancestors are affiliated. One year later, Keeler released Wesleyan University’s first repatriation policy, and a year after that, the 10 ancestors were finally able to return home to their decedent communities. While Honor Keeler left Wesleyan University shortly before the Ancestors returned home, the role of NAGPRA coordinator was not left empty. Wesleyan is currently working with Decedent communities and Tribes with the goal of repatriation the 5 remaining Ancestors in Wesleyan University’s care. In 2013, Wesleyan issued a public apology to Native Nations on its blog The Wesleyan Connection.

Since 2010, Wesleyan University has prioritized repatriation and education. Departments that are closely tied to museums, excavation, and indigenous history have incorporated lessons on NAGPRA into their courses in an effort to teach students about Wesleyan and, by extension, their own history. We now have a full-time position for an Archaeology Collections Manager/Repatriation Coordinator, and oversight of our repatriation compliance now rests with the Provost and Senior Vice President of Academic Affairs – this rightly situates our compliance at the university’s highest administrative levels.

Progress Made But…..

Wesleyans’ relationship with indigeneity has massively changed since the 1800s. This is reflected in the Wesleyan current treatment of Ancestors and its ongoing consultation efforts toward repatriation, in addition to its Tribe-centric approach to repatriation. Wesleyan as an institution has made significant improvements to its culture and compliance surrounding NAGPRA. A final NAGPRA Inventory for all Native American human remains in its control was submitted to the National Park Service in May 2024, and Notices of Inventory Completion are currently being drafted for publication in the Federal Register – these are the formal documents that will enable their return. However, I believe that the university needs to take the next step and practice not only the letter of the law, which it dose quite well, but the spirit of the law as well. This can be accomplished by putting more effort into community outreach and emphasizing that memory can be a form of informal repatriation.

The next step on Wesleyan’s NAGPRA journey is to further educate students of the campus community on what NAGPRA is, why it matters, and how it ties into Wesleyan past, present, and future. Wesleyan history with the Ancestors not only belongs to the institution but to everybody who touches the institution, whether you’re a student, staff member, or simply a visitor, Wesleyan’s history is now interwoven with yours.

The spirit of NAGPRA is to return what has been taken physically and culturally through a process of collaboration. Memory as a restorative tool is not new. However, it is extremely difficult to implement. In this exhibit, I have tried to bring awareness to NAGPRA and, more importantly, the Ancestors who were and still are at Wesleyan. By remembering these ancestors and their stories, we are actively restoring their personhood.

I hope this brief exploration of Wesleyan’s past and present has inspired you to learn more and share these stories.

Resources To Learn More

If you want to learn more about NAGPRA or the repatriation process, I recommend reading or listening to some of the resources below.

A podcast produced by CBC examines “Stuff the British Stole” and how these thefts affect the communities where these stories, people, and objects were taken from. While the podcast does not touch on NAGPRA, it explores repatriation more broadly.

Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits: Inside the Fight to Reclaim Native America’s Culture

In his book, Chip Colwell explores Indigenous leaders’ 5 decade long quest to have museums repatriate stolen objects and Ancestors. As a curator of anthropology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, Colwell has navigated NAGPRA firsthand.

Journeys to Complete the Work… And changing the way we bring Native American ancestors home

Co-written with Shannon Martin and the Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabe Culture & Lifeways this comic book is a great way to learn more about NAGPRA 10.11 and pays special attention to what the term “culturally unidentifiable individuals” means and how it impacts Native American Communities

Skull Wars

David Hurst Thomas explores the relationship between Native Americans and scientific archeology through the lens of the Kennewick Man case.

Works Cited

Exhibit Objects

Atalay, S., Shannon, J. A., & Swogger, J. (2017). Journeys to complete the work: Stories about repatriations and changing the way we bring Native American Ancestors Home.

Brivic, Max. University to Repatriate Native Remains and Relics. Middletown: The Wesleyan Argus, 2010.http://wesleyanargus.com/2010/11/16/university-to-repatriate-native-remains-and-relics/ .

Carlisle, Kate. (2013, April 8). Wesleyan apologizes to Native Nations, launches repatriation effort. newsletter.blogs.wesleyan.edu. https://newsletter.blogs.wesleyan.edu/2013/11/08/repatriationeffort/

Drake, S. G. (1837). Biography and history of the Indians of North America … : comprising details in the lives of all the most distinguished chiefs … Also, a history of their wars … With an account of their antiquities, manners and customs, religion and laws ; likewise exhibiting an analysis of the most distinguished, as well as absurd authors, who have written upon the great question of the first peopling of America … (7th ed., with large additions and corrections, and numerous engravings.). Antiquarian Institute.

Sponsored by the Center for the Americas, Keynote by Suzan Shown Harjo, “The Native American Graves Protection and and Repatriation Act Revisited: Negotiating Culture, Legalities, and Challenges.” Public Affairs Center (PAC) Room 001. November 4, 2016., November 4, 2016, Box: 12, Item: 99. Wesleyan University campus events and activities posters, 1999-072. Special Collections & Archives.

Secondary Sources

Atalay, S. (2018). Repatriation and bearing witness. American Anthropologist, 120(3), 544–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13079

Blakey, M., Lippert, D., Martin, S., Watkins, R., Atalay, S. (2021). Reclaiming the Ancestors: Indigenous and Black Perspectives on Repatriation, Human Rights, and Justice. . Sapiens.https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/reclaiming-the-ancestors/

Colwell, C. (2019). Plundered skulls and stolen spirits: Inside the fight to reclaim Native America’s culture. The University of Chicago Press.

DeLeary,L and Blais,D.[missingmatoaka]”Missing Matoaka.”SoundCloud, june 20,2022

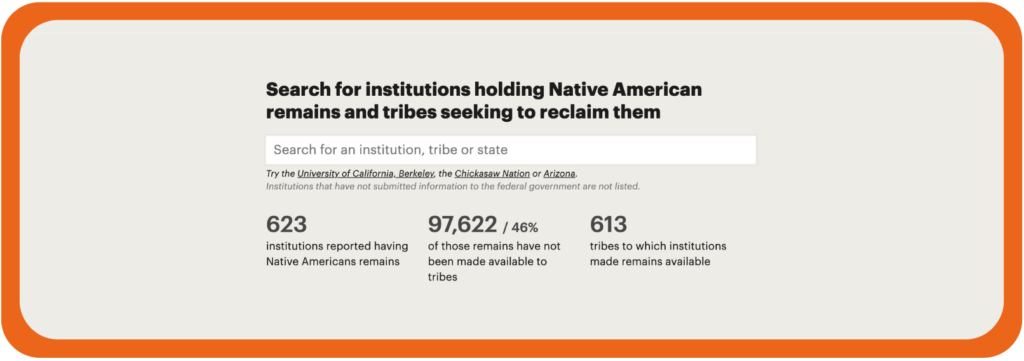

Feilds, A., Hudetz, M., Jaffe, L., & Ngu, A. (2023, January 11). The repatriation project. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/series/the-repatriation-project

Greer, E. Sunny. (2017). A Call for Healing from the Tragedy of NAGPRA in Hawaii. In Accomplishing NAGPRA, Oregon State University Press, Corvallis pp. 99-113.

Halliday, W. (n.d.). After departure of NAGPRA Coordinator, university plans for future of repatriation efforts. The Wesleyan Argus. http://wesleyanargus.com/2019/05/30/after-departure-of-nagpra-coordinator-university-plans-for-future-of-repatriation-efforts/

Hemenway, Eric. (2017). Finding Our Way Home. In Accomplishing NAGPRA, Oregon State University Press, Corvallis pp. 83-98.

King, T. L. (2019). The black shoals : offshore formations of Black and Native studies. Duke University Press.

Lonetree, A. (2012). Decolonizing museums: Representing Native America in national and Tribal Museums. University of North Carolina Press.

Nation Parks Service. (2012). Notice of Inventory Completion: Wesleyan University, Middleton, CT(Document Citation No.77 FR 39505).

Native knowledge 360°-the impact of words and tips for using appropriate terminology: Am I using the right word?. National Museum of the American Indian | Smithsonian. (n.d.). https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/informational/impact-words-tips

Ngu, A., & Suozzo, A. (2023, January 11). Does your local museum or university still have Native American remains?. ProPublica. https://projects.propublica.org/repatriation-nagpra-database/#:~:text=The%20University%20of%20California%2C%20Berkeley,at%20least%201%2C800%20Native%20Americans

Riding In, James, Cal Seciwa, Suzan Shown Harjo, and Walter Echo-Hawk. (2004).Protecting Native American Human Remains, Burial Grounds, and Sacred Places [Panel Discussion]. Wicazo Sa Review 19(2):169-183.

U.S. Department of the Interior. (n.d.). Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act Glossary. National Parks Service. https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nagpra/glossary.htm